Shakyamuni in Tibetan Buddhism: The Color and Spiritual Code of the Enlightened One

wudimeng-Jan 07 2026-

0 Kommentare

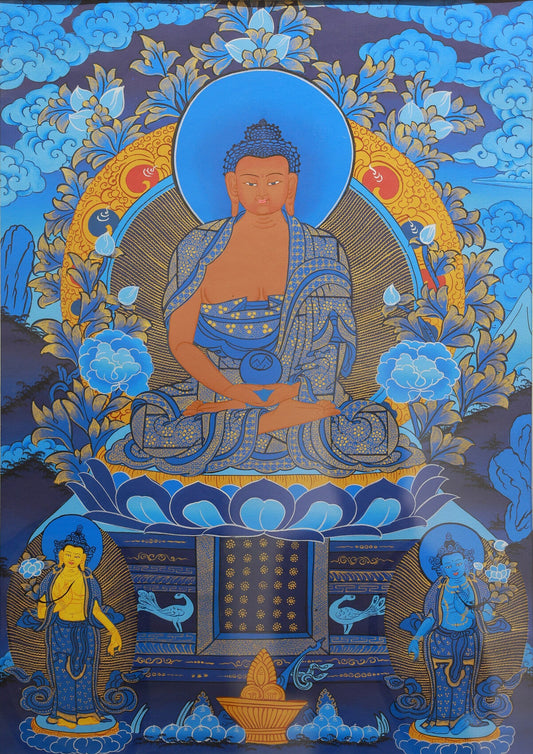

When the faint glow of a butter lamp brushes over the lapis lazuli and cinnabar-blended lotus petals on a thangka, what we gaze upon is not just a work of religious art painted with mineral pigments—but the embodiment of the spirit of “enlightenment” in Tibetan Buddhism. This is the millennia-old wisdom carried by the Thanka of Shakyamuni Buddha’s Life. In the belief system of Tibetan Buddhism, Shakyamuni is never reduced to a distant historical figure; instead, through thangka iconography, ritual festivals, and the transmission of teachings, he becomes a living symbol of “compassion and wisdom.”

1. Buddha’s Body and Attire: The Visual Language of Compassion and Wisdom

The main figure’s orange-yellow skin is the standard hue for the “Buddha’s body color” in Tibetan iconography, symbolizing “compassion that shines on all beings like sunlight.” The kasaya (monastic robe) is decorated with red-gold interwoven patterns: red, derived from Tibetan cinnabar, represents “vigor to overcome afflictions”; gold, a mineral pigment mixed with pure gold powder, signifies “unchanging wisdom.” The style of the robe (exposing the right shoulder) originates from the traditions of Indian monastic communities, reflecting both “accommodation to worldly customs” and the enlightened quality of “not clinging to external forms.”

2. Mudras and Ritual Implements: Concrete Symbols of Teachings

The Dharma Wheel Jewel held in the Buddha’s left hand symbolizes the “First Turning of the Dharma Wheel”—the wheel’s eight spokes correspond to the “Noble Eightfold Path,” and the jewel represents the “perfect fruition of Buddhahood.” The lotus throne on which Shakyamuni sits cross-legged is a core symbol in Tibetan iconography: the lotus root sinks into mud while the flower blooms in purity, just as Shakyamuni attained enlightenment from the mundane world and uses his teachings to liberate beings from afflictions.

3. Attendants and Background: The Genealogy of Teaching Transmission

The two bhikkhus below the main figure are Shakyamuni’s chief disciples: Shariputra (foremost in wisdom) and Maudgalyayana (foremost in supernatural powers). Holding a khakkhara (monastic staff) and a sutra scroll, they represent both the “model of disciples who attained enlightenment through listening to the Dharma” and the implication that “teachings must be transmitted across generations.” The background’s blue-green peonies and colorful clouds are not mere decorations: in Tibetan Buddhist context, peonies symbolize “the union of prosperity and liberation,” while the vibrant auspicious clouds correspond to the canonical account of “heavenly flowers falling when the Buddha preached.”

II. Core Teachings: Shakyamuni’s Enlightenment and Dharma

Faith in Shakyamuni in Tibetan Buddhism revolves around “how he attained enlightenment and how he transmitted the Dharma”—these teachings are the spiritual core of thangka iconography.

1. The First Turning of the Dharma Wheel: The Middle Way from Suffering to Liberation

The “Four Noble Truths” and “Noble Eightfold Path” that Shakyamuni expounded to the Five Ascetics in Deer Park are the foundational teachings of Tibetan Buddhism, known as the “First Turning of the Dharma Wheel.” The Dharma Wheel Jewel in this thangka commemorates this event:

-

Four Noble Truths: Suffering (all sentient beings experience suffering), Origin (suffering arises from afflictions), Cessation (afflictions can be ended), Path (liberation through the Noble Eightfold Path);

-

Noble Eightfold Path: Right View, Right Intention, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, Right Concentration—this is the practical framework for “dual practice of calm abiding and insight” in Tibetan Buddhism, and remains the core of monastic practice today.

In Tibetan monasteries, the “Dharma Wheel Turning Day” (15th day of the 4th Tibetan month) features grand ceremonies: monks recite the Sutra of the Turning of the Dharma Wheel, and devotees offer lamps to pray, commemorating the moment Shakyamuni “opened the door to wisdom for all beings.”

2. Descent from the Heavens Day: The Enlightened One’s Filial Piety and Practice

The “Descent from the Heavens Day” (22nd day of the 9th Tibetan month) is a Tibetan Buddhist festival commemorating Shakyamuni’s return to the human realm after preaching to his mother in the Trayastrimsa Heaven. It has become a key opportunity for devotees to practice Shakyamuni’s teachings:

-

Lamp Offering: Thousands of butter lamps symbolize “dispelling the darkness of ignorance,” echoing Shakyamuni’s vow to “illuminate all beings with wisdom”;

-

Liberation of Living Beings: Redeeming creatures destined for slaughter upholds the precept of “non-harm” and is a direct way to cultivate “unconditional great compassion”;

-

Eight Precepts Observance: Abstaining from eating after noon and refraining from entertainment to experience a renunciate’s life—this is the contemporary practice of the “Middle Way” that Shakyamuni advocated after his ascetic period.

III. Thangka Art: The Intangible Heritage Carrier of the Enlightenment Spirit

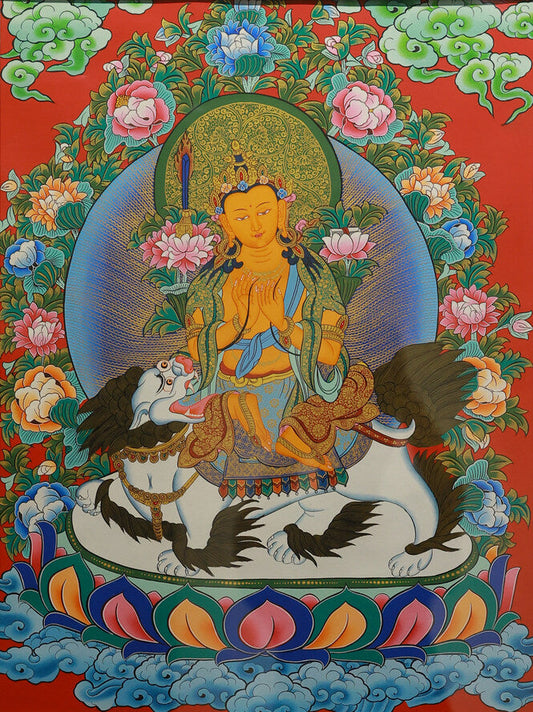

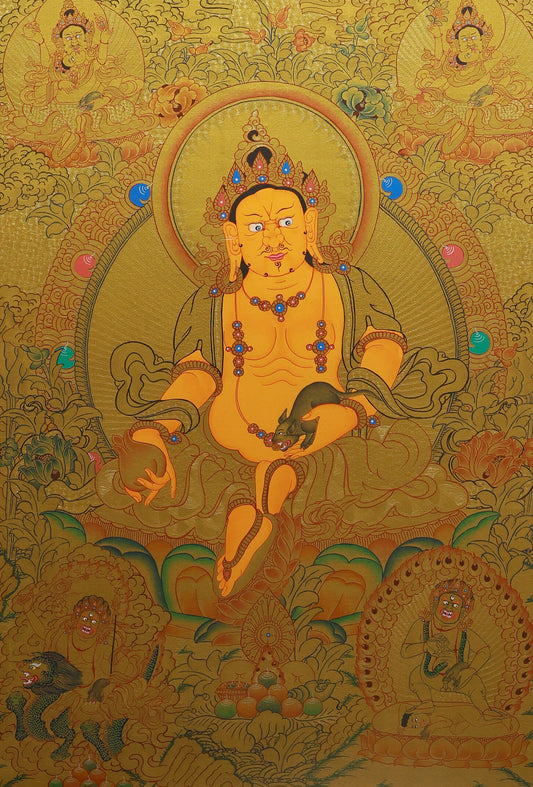

This thangka belongs to the Regong Thangka school; its “mineral pigment + hand-painted gold thread” technique is not just an artistic tradition, but an interpretation of Shakyamuni’s “enduring” spirit.

1. Fade-Resistant Pigments: The Materialization of Faith

The lapis lazuli (blue), cinnabar (red), and gold powder (yellow) used by painters are all natural minerals from the Tibetan Plateau. These pigments undergo “three grindings, three filtrations, and three sun-dryings” before they can be applied to the thangka, where they remain vivid for millennia. Just as Shakyamuni’s teachings have stayed alive for over 2,000 years, the “fade resistance” of mineral pigments is a material metaphor for the “unchanging nature” of faith.

2. The Craftsmanship of Regong Intangible Heritage: Contemporary Practice of Enlightenment

Regong thangka painters must study the Iconometric Canon for months before picking up a brush—every curve of a line and every shade of color must conform to ritual rules. This creative approach of “revealing solemnity through discipline” mirrors Shakyamuni’s teachings: using clear precepts and stages to guide beings from distraction to enlightenment.

Today, inheritors of the Regong Thangka intangible heritage also apply this technique to public welfare: teaching simplified thangka painting to disabled students, allowing the spirit of “liberating all beings” to continue in a modern way.

IV. Shakyamuni in the Tibetan Context: More Than a Buddha, a Spiritual Compass

In Tibetan Buddhism, Shakyamuni is not the “only Buddha,” but the “paragon of enlightenment”—his life stories, teachings, and festivals form the spiritual framework of devotees’ lives:

- Monks recite the Praise to Shakyamuni Buddha in their daily morning chanting;

- Every household shrine includes a statue of Shakyamuni;

- Pilgrims prostrate all the way to Lhasa, with the ultimate aspiration of “attaining enlightenment like Shakyamuni.”

What this thangka presents is such a three-dimensional Shakyamuni: he is a solemn icon in art, an enlightened teacher in teachings, a guide for practice in festivals, and a spiritual beacon for Tibetan beings “moving from the mundane to liberation.”

#TibetanBuddhism #Shakyamuni #ThangkaArt #RegongIntangibleHeritage #FirstTurningOfTheDharmaWheel #DescentFromTheHeavensDay #IconometricCanon #BuddhistTeachings #EnlightenmentSpirit #MineralPigmentThangka