Tibetan Buddhist Mandala: A Visual Poem of Cosmic Order, the Enlightenment Code Hidden in Geometry

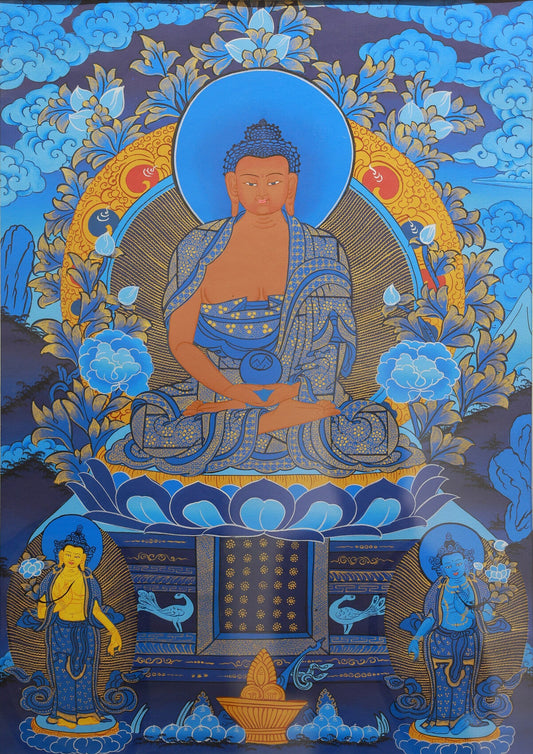

When you gaze at a Tibetan Buddhist mandala (from the Sanskrit mandala), you are not looking at a mere geometric pattern—it is a "spiritual universe" built with color and line: the central deity resides in a palace like Mount Meru, the four gates correspond to the Four Noble Truths, the outer flames and lotus flowers form a 结界 (protective barrier), and even the color of each grain of sand aligns with the wisdom of the Five Dhyani Buddhas. In Tibetan Buddhism, the mandala is both a materialization of the Buddha’s realm and a "spiritual map" for practitioners to visualize enlightenment.

I. The Origin of the Mandala: From Indian Altar to the "Sacred Vessel" of the Buddha’s Realm

The Sanskrit term mandala originally referred to the square and circular earthen altars used in ancient Indian rituals—where people demarcated sacred spaces to ward off "demonic disturbances" during ceremonies. After Buddhism emerged, this form took on a new spiritual core: it was no longer a secular altar, but a "gathering place of all sages and merits," a "dharma field" where Buddhas and Bodhisattvas descend.

In Tibetan, the mandala is called dkyil-hkhor (literally "center and periphery")—centered on the principal deity, surrounded by attendants, ritual implements, and symbols in layers, forming a "perfectly rounded" order. This order aligns with Buddhist cosmology: the center symbolizes Mount Meru, the four gates correspond to the Four Great Continents, and the outer circle signifies "wholeness without deficiency." As the Vajraśekhara Sūtra states: "A mandala is the meaning of wholeness, taking perfect completeness as its essence."

Tracing its historical evolution, the mandala developed alongside esoteric Buddhism:

- Early stage: Simple earthen altars and symbols, used for initiation ceremonies;

- Tang Dynasty (China): Introduced to China with Esoteric Buddhism, evolving into 2D forms like thangkas and murals;

- Tibetan period: Combined with Bön culture, giving rise to diverse forms such as sand paintings and three-dimensional castings (e.g., the colored sand mandala at Tashilhunpo Monastery, and the gold-inlaid turquoise mandala in the Forbidden City).

II. The Structure of the Mandala: Every Line is a Metaphor for Enlightenment

The structure of a Tibetan Buddhist mandala follows strict esoteric rituals, with each element carrying specific symbolic meaning. Taking the mandala in the opening image as an example, its structure can be broken down into a cosmic model of "three protective barriers + core palace":

1. Outer Barriers: From Chaos to Purification

- Fire wheel: The outermost flame pattern symbolizes "renunciation"—burning worldly afflictions and warding off external demons;

- Vajra wheel: A ring of three-pronged or five-pronged vajras, representing the "indestructible Bodhicitta" (enlightenment mind), serving as a spiritual armor for practitioners;

- Lotus petals: Radiating inward, lotus petals symbolize "purity untainted," echoing the Vajraśekhara Sūtra’s teaching that "the lotus grows from mud yet remains unstained."

2. Middle Palace: Sacred Order in Symmetry

The square pavilion with four gates is the core carrier of the mandala:

- Four gates: Corresponding to the Four Noble Truths (suffering, origin, cessation, path), the dharmachakra (wheel of dharma) flanked by deer above each gate symbolizes the Buddha’s first sermon at Sarnath;

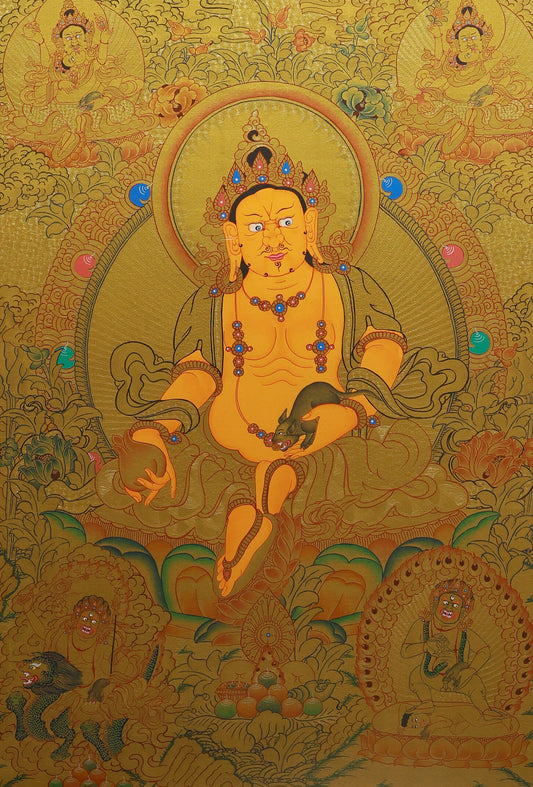

- Four colors: The blue, yellow, red, and green of the walls correspond to the Five Dhyani Buddhas (white for the central Buddha) of the four cardinal directions—each color represents a "Buddha wisdom" (e.g., blue corresponds to the "mirror-like wisdom");

- Arrangement of attendants: Deities and protectors in the pavilion are arranged in concentric circles or radiating patterns, reflecting the "hierarchical order" of the Buddha’s realm, and also metaphorizing the practitioner’s goal of "uniting one’s mind with the principal deity."

3. Central Deity: The "Abode of the Mind" for Enlightenment

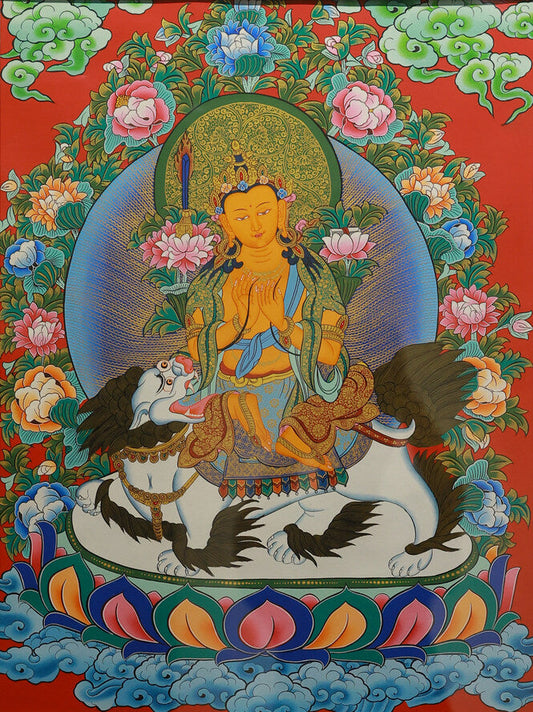

The innermost circular area is where the principal deity (e.g., Kalachakra, Manjushri) resides:

- Central wheel: Often painted with an eight-spoked dharma wheel or a grid pattern, symbolizing the "turning of the dharma wheel" and the "emptiness of all phenomena";

- Implements and symbols: The vajras, vases, etc., held by the deity embody the samaya mandala—using objects to represent vows, signifying the deity’s aspirations and blessings.

III. Sand Mandala: A Spiritual Ritual That Interprets "Impermanence" Through Destruction

In Tibetan Buddhism, the most striking form of the mandala is the colored sand mandala—a spiritual practice of "construction as deconstruction," perfectly embodying the Buddhist essence of "all conditioned things are impermanent."

1. Creation: Devotion in a Million Grains of Sand

Creating a sand mandala requires the collaboration of several monks, taking days to months:

- Material preparation: Grinding gold, turquoise, agate, and other ores into fine sand, blending 14 colors (5 base colors + 9 gradients) corresponding to the Five Dhyani Buddhas and different attendants;

- Positioning: Using vertical and diagonal lines to mark the geometric framework on the pedestal, ensuring each line’s error is no more than 1 millimeter;

- Painting: Starting from the center and moving outward, pouring colored sand slowly from horn tubes to fill the patterns—each grain’s placement follows esoteric rituals, allowing no mistakes.

2. Destruction: A Lesson in "Emptiness" Through Ephemeral Beauty

After completion, the mandala is only displayed for a few hours before monks sweep it away with brooms, pouring the sand into a river—this is not "destruction," but "return":

- The sand scattering with the current symbolizes "no-self," reminding practitioners not to cling to appearances;

- The cycle from "construction" to "destruction" is a tangible practice of "impermanence": all worldly things, like the mandala, arise from conditions and cease when conditions end.

As a monk from Tashilhunpo Monastery put it: "The beauty of the sand mandala lies precisely in its disappearance—that is its most profound meaning."

IV. The Spiritual Significance of the Mandala: "The Self is the Universe" in Visualization

For esoteric practitioners, the mandala is a core tool for visualization—by focusing on or meditating on its structure, they achieve the enlightenment of "uniting the self with the universe."

1. Steps of Visualization

The Kalachakra Tantra records three stages of mandala visualization:

- "Outer mandala" visualization: Viewing the mandala as an objectively existing Buddha’s realm, imagining oneself inside, paying homage to the deity;

- "Inner mandala" visualization: Projecting the mandala onto one’s body—the central deity corresponds to the heart, the four gates to the limbs, the lotus petals to the meridians, realizing "the body is the mandala";

- "Secret mandala" visualization: Transcending form, comprehending the mandala’s essence of "emptiness"—the self, the deity, and the mandala are indistinguishable, all manifestations of "the true nature of all phenomena."

2. The Mandala in Initiation

In esoteric initiation ceremonies, the mandala is an "energy medium between guru and disciple":

- The disciple must vow to uphold esoteric precepts before the mandala;

- The guru transmits the deity’s blessings by "visualizing the mandala merging into the disciple’s body and mind," marking the disciple’s formal entry into esoteric practice.

V. Contemporary Extensions of the Mandala: From Religious Symbol to Cross-Cultural Spiritual Carrier

Today, the mandala has transcended religious boundaries to become a cross-cultural spiritual symbol:

- Psychology: Carl Jung viewed the mandala as an embodiment of the "self archetype"—its symmetrical structure corresponds to the human subconscious need for integration. Modern mandala art therapy, derived from this, helps people alleviate anxiety and integrate inner conflicts;

- Art and design: Contemporary artists draw inspiration from the mandala’s geometric aesthetics to create abstract works; fashion and architecture also often borrow its symmetrical patterns to convey the idea of "wholeness and harmony";

- Environmental practice: Some create mandalas with biodegradable materials, sowing seeds after destruction—transforming the metaphor of "impermanence" into an ecological concept of "endless renewal," giving the mandala new contemporary meaning.

Conclusion: The Mandala is a Mirror Reflecting the Self

The Tibetan Buddhist mandala is never a "distant Buddha’s realm," but a "map of the inner universe"—it uses geometric order to mirror the chaos and clarity in the practitioner’s mind; it uses the destruction of sand painting to remind people to cherish the wholeness of the present.

Next time you see a mandala, pause for a moment: behind those lines and colors, millennia of wisdom whisper—the order of the universe lies within your heart.

#TibetanBuddhistMandala #MandalaSymbolism #SandMandala #BuddhistCosmology #EsotericSpirituality #ImpermanencePhilosophy #JungianMandala #ReligiousArt #SpiritualHealing #TibetanCulturalSymbol

Schlagwörter:

Vorherige

Emerald Compassion: The Belief in Green Tara in Tibetan Buddhism and the Art of Color Thangka

Nächste

Mandala in Tibetan Buddhism: The Cosmic Order Frozen in Color