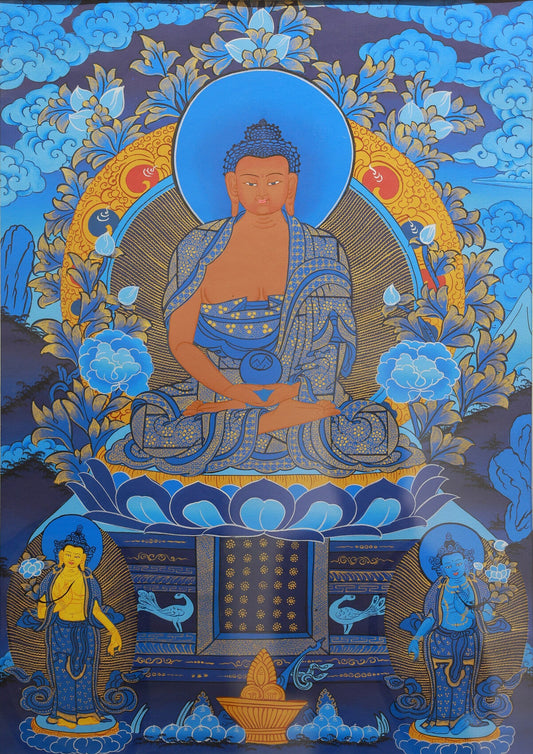

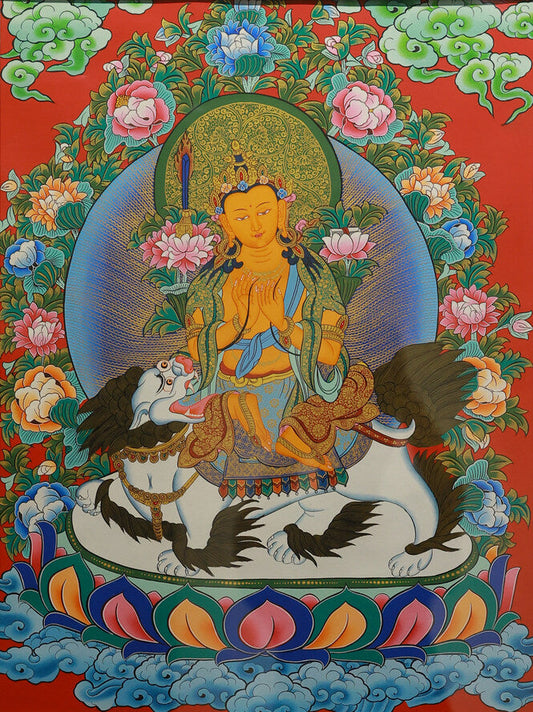

When a richly colored, intricately detailed Tibetan Thangka unfolds before your eyes, it’s hard not to be drawn to the dignified, softly gazed goddess at its center: adorned with jewels and floral wreaths, seated half-lotus on a pink lotus throne, with seven eyes on her forehead, palms, and soles of her feet calmly observing the world. This is White Tara—one of the most revered female buddhas (Taras) in Tibetan Buddhism.

White Tara’s image pervades Tibetan life: lining prayer paths, in household shrines, and in monastery halls. She is the "compassionate mother who rescues from suffering" to devotees, a sacred subject that Thangka painters render with devotion, and the tangible embodiment of compassion in Tibetan Buddhism. Using this Thangka as a key, this article unlocks White Tara’s origin, symbolic iconography, spiritual core, and her millennium-long living heritage in Tibetan culture.

In Tibetan Buddhism’s pantheon, "Tara" refers to female buddhas emanated from the compassionate heart of Avalokiteshvara, meaning "she who delivers sentient beings from suffering." White Tara, one of the most central Taras, is also known as the "Seven-Eyed Tara" or "Tara Who Delivers from the Eight Perils."

Her origin is a shared narrative across Tibetan Buddhist schools: When Avalokiteshvara wept at the weight of sentient beings’ suffering, his left tear became Green Tara, and his right tear became White Tara. Inheriting Avalokiteshvara’s compassionate vows, the two Taras take a female form that feels closer to sentient beings, fulfilling the pledge to "deliver all from worldly suffering." In The Origin of Tara, White Tara is further regarded as an emanation of Amitabha Buddha (or intrinsically linked to him), her pure nature aligning with the vows of Amitabha’s Western Pure Land.

White Tara holds a core position in schools like Gelug, Sakya, and Nyingma: She is a protector of the Gelug school’s Je Tsongkhapa, a key practice in the Sakya school’s "Path and Fruit" teachings, and the Nyingma school’s terma (revealed treasure) texts preserve numerous White Tara rituals and prayers. To devotees, she is not a distant deity, but a spiritual anchor like a loving mother, ready to answer prayers at any time.

Tibetan Thangkas are devotional objects of "liberation upon sight," where every detail carries sacred meaning. Taking this Thangka as an example, White Tara’s image visually expresses her compassion and redemptive power:

White Tara’s most distinctive marker is the seven eyes on her forehead, palms, and soles. These are not mere decorations, but symbols that she "observes the sufferings of all sentient beings across the ten directions and three times"—no matter a being’s circumstance or time, they are covered by her compassionate gaze. Tibetans often say: "White Tara’s eyes are brighter than the stars; they see every hardship a person bears."

In the Thangka, White Tara sits in the "half-lotus (lalita) posture" on a double-layered pink lotus throne: her left leg curled inward, right leg hanging naturally. This posture balances the solemnity of a buddha/bodhisattva with approachability. The pink lotus symbolizes "purity" in Tibetan Buddhism, signifying that White Tara’s compassionate vows arise from an untainted mind, unblemished by worldly afflictions.

Her right hand forms the Varada Mudra (gesture of granting wishes: palm outward, fingers slightly curved), a symbol of "fulfilling all good wishes of sentient beings"—when devotees pray for health or safety, this mudra is White Tara’s promise of response. Her left hand holds an utpala (blue lotus) at her chest; the stem extends to her shoulder, with a wisdom dharma wheel resting on the bloom: the blue lotus represents a pure mind, the dharma wheel symbolizes the Dharma’s power to crush afflictions, and their combination embodies Tibetan Buddhism’s core teaching of "compassion paired with wisdom."

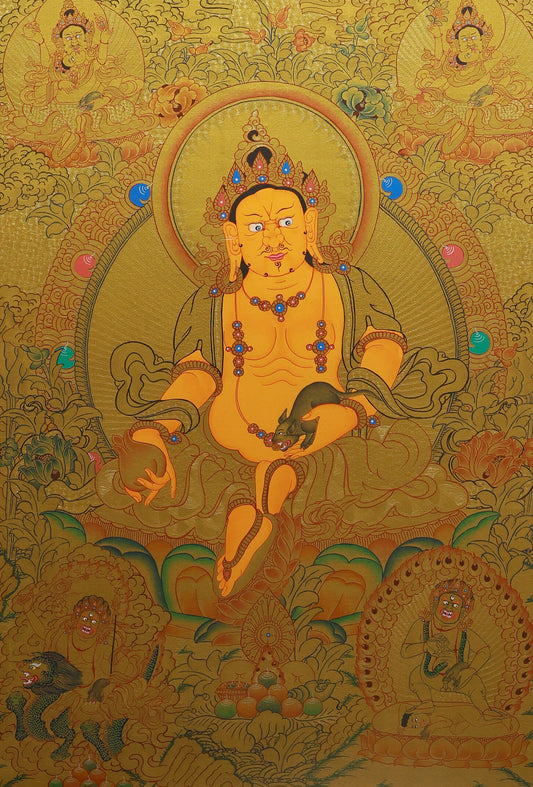

White Tara’s jewel ornaments and floral crown are visual symbols of "perfect merit and wisdom"; the background’s auspicious clouds (signs of the pure land), lush trees (nourishment of compassion), and the root buddha (usually Amitabha) above collectively construct a "pure land permeated with compassion," implying her deliverance guides sentient beings toward pure liberation.

The golden, benevolent attendant and the deep blue, solemn attendant on either side symbolize "gentle and wrathful aspects"—gentle comfort and overcoming obstacles, both ultimately serving the core vow of "freeing sentient beings from suffering."

In Tibetan Buddhist devotion, White Tara’s "compassion" is not an abstract concept, but a living force integrated into devotees’ lives:

White Tara is called the "Tara Who Delivers from the Eight Perils," where the "Eight Perils" are hardships common to Tibetan devotees: lion peril (wild animal harm), elephant peril (giant beast threat), snake peril (poisonous bites), water peril (drowning), fire peril (burning), thief peril (robbery), non-human peril (evil spirit harassment), and prison peril (punishment and detention). The Heart Sutra of White Tara clearly states: "Those who recite my name shall be freed from the Eight Perils"—this concrete protection makes her the most trusted guardian of Tibetan people.

"Om Tare Tuttare Ture Soha" is White Tara’s root mantra, known to nearly every Tibetan devotee. Recited during morning circumambulations, bedside prayers, or travel blessings, this mantra is the bond linking devotees to her vows. In monastery rituals, devotees align with White Tara’s compassionate field by prostrating to the Thangka, lighting butter lamps, and reciting while visualizing her form.

In Tibetan Buddhism’s pantheon, female buddhas like White Tara are not "attachments," but "feminine emanations of compassion and wisdom." Her female form allows female devotees to feel "motherly compassion" more intuitively, making her the warmest spiritual support during childbirth, parenting, and family hardships.

White Tara’s devotion has long transcended religious rituals to become part of Tibetan culture:

Painting a White Tara Thangka is a "devotional practice": artists first fast and recite mantras, then outline proportions strictly according to the Iconometric Canon—no errors are allowed in body measurements, seven-eye placement, or mudra angles. A single Thangka may take months to years to complete, with every brushstroke of color infusing the artist’s compassion.

During the "Tara Festival" in the first month of the Tibetan calendar, monasteries display giant White Tara Thangkas, and devotees dress in finery, hold butter lamps, and circumambulate while praying. During Tibetan New Year, families clean their White Tara Thangkas, offer butter sculptures and barley wine, and pray for peace and prosperity.

White Tara’s image can be found in Tibetan farmhouses, nomadic tents, and urban Tibetan cafes—she has moved from monasteries into mundane life, becoming a symbol of "steadfast peace."

Gazing at White Tara in this Thangka, we see not just a female buddha of Tibetan Buddhism, but a spiritual symbol of "compassionate care": her seven eyes observe all suffering, and her Varada Mudra answers all good wishes.

In today’s world, this compassion holds universal meaning: looking at others’ hardships with gentle eyes, and responding to their needs with concrete action—this is the value of White Tara’s devotion that transcends religion and culture. And the quietly hung Thangka is a testament that "compassion is never far away."

#WhiteTaraInTibetanBuddhism #WhiteTaraThangkaSymbolism #WhiteTaraEightPerilsVows #TibetanFemaleBuddhaCulture #ThangkaArtAndFaithHeritage #TibetanThangkaArt #SevenEyedTara #TibetanBuddhistDevotion