Cai Tang Vaishravana: The Guardian of Wealth in Tibetan Buddhism, The Golden Faith in Thangka Art

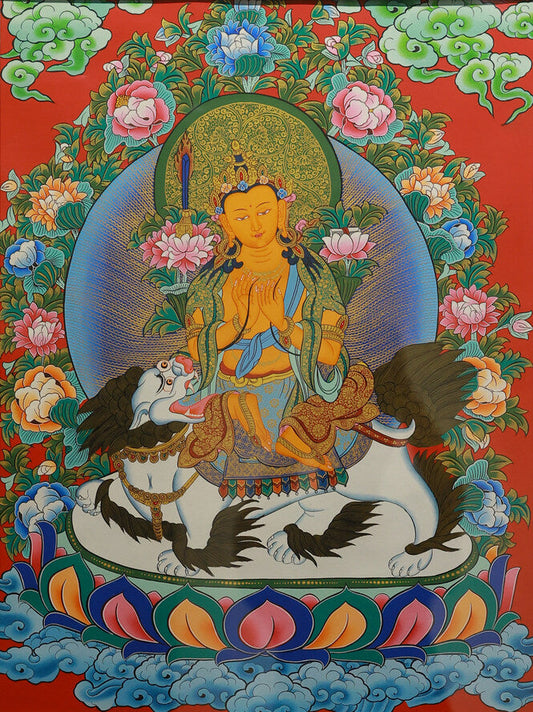

When a vivid, intricately lined Cai Tang Thangka unfolds before your eyes: a deity seated on a snow lion against a bright yellow background, holding a victory banner aloft, with a treasure-spitting rat leaping in his arms and jewels scattered like stars around him—this is the widely revered Cai Tang Vaishravana in Tibetan Buddhism. He is both Vaishravana, the Northern Heavenly King who protects the Dharma, and a spiritual symbol that carries people’s wishes for good fortune. Today, we start with this Thangka to decode its artistic secrets and spiritual core.

I. Cai Tang Thangka: An Epic of Mineral Colors on Tibetan Canvas

In Tibetan Buddhist art, Thangkas are visual dharma gates for "liberation upon sight," and Cai Tang (color Thangka) is the most visually striking of the three main Thangka categories (Cai Tang, line-drawing Thangka, black-gold Thangka)—using rich, vibrant mineral pigments to embody the deity’s majesty and good fortune on canvas.

1. Pigments: Colors Ground from "Treasures of Mountains and Rivers"

The reason Cai Tang’s colors remain vivid for millennia lies in its "luxurious" raw material base: artists use minerals and gemstones such as cinnabar (red), azurite (blue), malachite (green), and gold leaf, supplemented by plant dyes like saffron and rhubarb, to make pigments through multiple processes:

- First, remove impurities from the ore, crush it, and rinse it repeatedly with clean water four or five times until the water clears;

- Then grind it by hand—azurite must be ground to a fine powder to separate shades like "primary blue" and "secondary blue"; gold leaf must be hammered thin as a cicada’s wing to adhere to the canvas;

- Finally, mix with bone glue and separate shades using the "water-flying method" to ensure color saturation and layering.

For example, in this Cai Tang, the snow lion’s green mane is made from malachite-ground green pigment, while the red patterns on the victory banner are a combination of cinnabar and gold leaf—every hue is a crystallization of mountain treasures and devout human effort.

2. Craftsmanship: Devotional Creation Measured by the Iconographic Measurement Sutra

Cai Tang painting is never random artistic creation, but follows the religious rituals of the Iconographic Measurement Sutra:

- Drafting requires charcoal to outline the deity’s proportions, ensuring the form aligns with the "thirty-two marks and eighty secondary characteristics" of enlightened beings;

- Line work uses wolf-hair brushes, with smooth, delicate lines—every pattern on the victory banner and every hair on the snow lion must be precise;

- Coloring and shading follow the rule of "from dark to light, from background to subject," layering colors to create a three-dimensional effect;

- The most critical "face-opening" process must be completed by a practicing artist—the majestic wide eyes and the subtle compassion at the corners of the mouth must be executed in one stroke, because "opening the face is endowing the soul," the core of the Thangka’s "liberation upon sight."

II. Vaishravana: From "Northern Heavenly King" to Tibetan Buddhism’s "God of Wealth and Protection"

The yellow-bodied deity before you is not merely a "god of wealth"—he is the Sanskrit "Vaiśravaṇa," the Northern Heavenly King among Buddhism’s Four Heavenly Kings, and the manifestation of Ratnasambhava Buddha (the Southern Buddha) in Tibetan Buddhism, holding dual identities as a "Dharma protector" and a "god of wealth."

1. The "Symbolic Code" of His Form (Based on This Cai Tang)

- Yellow Body: Corresponding to Ratnasambhava Buddha’s "yellow Buddha realm," it symbolizes increasing good fortune and accumulating virtuous karma, serving as a visual symbol of "wealth and merit" in Tibetan Buddhism;

- Mount Snow Lion: A Tibetan mythical beast with green mane and white body (painted with malachite green and mineral white pigments), its four claws represent the four immeasurables (loving-kindness, compassion, joy, equanimity)—symbolizing both the fearlessness to subdue demons and the ability to spit out treasures to relieve sentient beings;

- Victory Banner (Dhvajra): Also called the "banner of triumph," its red and gold patterns (cinnabar + gold leaf) symbolize overcoming afflictions, protecting the Dharma, and also represent favorable weather and stable undertakings;

- Treasure-Spitting Rat (Nüli) in His Arms: A retinue of the dragon king, originally living in the sea, it can transform what it eats into treasures and spit them out—it is a symbol of abundant wealth, and when worshipped, it requires offerings of the "three whites (milk, cheese, flour)" and "three sweets (sugar, honey, rock sugar)," embodying the wish for "pure wealth";

- Jeweled Adornments: Necklaces, gold bracelets, and other ornaments cover his body, reflecting the deity’s dignity and symbolizing the state of "perfect good fortune."

2. The "Duality" of His Identity: More Than a God of Wealth, a Dharma Protector

Vaishravana originally was Kubera, the god of wealth in Indian mythology; after integrating into Buddhism, he became the Northern Heavenly King, guarding the crystal palace north of Mount Sumeru. After spreading to Tibet, he was endowed with the identity of "manifestation of Ratnasambhava Buddha"—he is both a Dharma protector (Gelug sect founder Tsongkhapa received his blessing to build monasteries) and the "lord of the eight directional wealth gods," leading the eight paths of wealth—this is his dual function of "subduing evil and bestowing good fortune."

III. Vaishravana in Cai Tang: Every Stroke Is the "Materialization of Faith"

For Tibetans, the Cai Tang Vaishravana Thangka is not a "decorative painting," but a "carrier of practice and wishes"—every stroke of the Thangka is the "materialization of faith."

1. The Religious Function of Thangkas: A Visual Dharma Gate for Liberation Upon Sight

Tibetan Buddhism holds that visualizing the 本尊 in a Thangka is equivalent to establishing a spiritual connection with the deity—in this Cai Tang, Vaishravana’s majestic form can subdue the inner "greed, anger, and delusion," the treasure-spitting rat and jewels evoke the wish for "pure wealth," and the snow lion’s fearless posture hints at "overcoming obstacles."

2. Localized Expression of the Scene

The Tibetan landscape (rolling hills, sparse vegetation) in the Thangka’s background is the artist’s way of localizing the "Indian deity"—linking Vaishravana’s protection to Tibetans’ daily lives, making it easier to evoke emotional resonance. The scattered jewels are not "showing off wealth," but symbolize that "Vaishravana can bestow boundless good fortune on all sentient beings."

IV. Devotional Practices of Vaishravana: From Monasteries to Secular Life—Wishes for Good Fortune

Vaishravana’s worship has long been integrated into Tibetans’ lives—from monastery protector halls to herders’ tents, and even merchants’ shops, he is the link between "virtuous karma and wealth."

1. Worship in Monasteries

In the protector halls of Tibetan monasteries, Vaishravana is often worshipped alongside the Eight Horse Kings (eight directional wealth gods): he sits in the center, while the eight wealth gods oversee wealth from all directions, forming a belief system of "protecting the Dharma + bestowing good fortune." When believers pay homage, they offer clear water, incense, and butter lamps, and recite his mantra "Om Vaiśravaṇa Ya Svāhā," praying for "growing virtuous karma and abundant wealth."

2. Secular Wishes

- During the Tibetan New Year, herders hang Vaishravana Thangkas in their tents and offer the "three whites and three sweets," praying for prosperous cattle and sheep in the coming year;

- Merchants hang Thangkas in their shops, praying for smooth business—yet Tibetan Buddhism emphasizes: "The wealth sought must be used for the benefit of others to receive blessings," which is the wisdom of "using wealth for good."

V. The Contemporary Value of Cai Tang Vaishravana: Dual Inheritance of Art and Faith

Today, the Cai Tang Vaishravana Thangka has long transcended the category of "religious items" and become a calling card for Tibetan culture to go global, holding dual value in art and spirit.

1. Intangible Cultural Heritage Inheritance of Art

Many areas in Tibet have listed Cai Tang Thangka as an intangible cultural heritage protection project and established inheritance bases: young artists learn traditional mineral pigment techniques and the norms of the Iconographic Measurement Sutra under the guidance of old artisans, while also incorporating contemporary aesthetics—for example, simplifying some complex patterns while retaining Vaishravana’s core symbols (victory banner, treasure-spitting rat, snow lion), allowing this ancient art to adapt to modern tastes.

2. Contemporary Resonance of Spirit

For modern people, Vaishravana’s "wealth wisdom" remains relevant: he is not a "god who satisfies greed," but a guide to "accumulating good fortune through virtuous karma"—material wealth is "provisions for practice," not an end. Only when obtained with a pure heart and used for the benefit of others can one truly achieve "the cultivation of both fortune and wisdom."

When we gaze at this Cai Tang Vaishravana Thangka, we see not just an artistic treasure painted with mineral pigments, but Tibetans’ understanding of "wealth and virtuous karma": wealth is not a goal, but a tool to protect life and practice compassion, and every color stroke of the Thangka is the visual expression of this wisdom.

#CaiTangVaishravana #TibetanBuddhismThangka #CaiTangThangkaCraftsmanship #VaishravanaSymbolism #TibetanCulturalArt #TraditionalThangkaArt #TibetanBuddhistWealthDeity #MineralPigmentThangka #TibetanIntangibleCulturalHeritage #BuddhistDevotionalArt #TibetanSpiritualArt

Schlagwörter:

Vorherige

Mandala in Tibetan Buddhism: The Cosmic Order Frozen in Color

Nächste

The Dragon Mandala in Tibetan Buddhism: A Three-Dimensional Poem of Divine Oracle and Cosmos