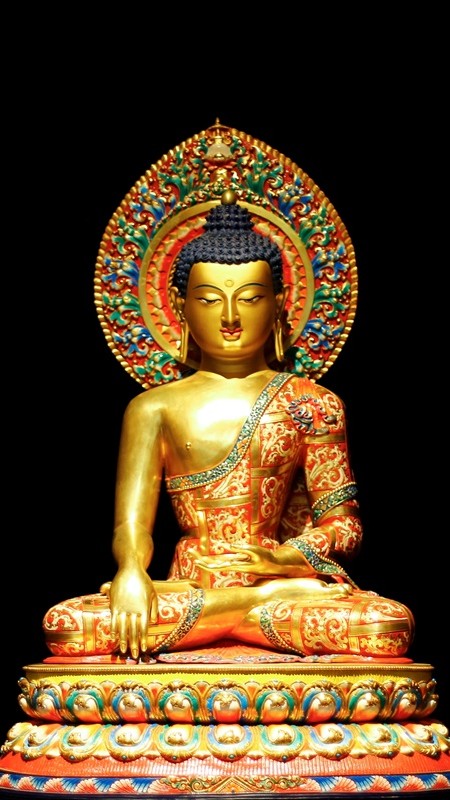

When a hand-painted Nepalese thangka, crafted with natural mineral pigments, unfurls in a shrine, it carries not just the spiritual symbols of Tibetan Buddhism, but the living heritage of Newari millennial painting craftsmanship. The 43x62cm "Yellow Jambhala (Main Deity) & Five Directional Wealth Deities" hand-painted thangka we focus on today is precisely such a work that merges religious doctrine with artistic ingenuity—it is both a tangible vessel of Tibetan Buddhism’s "Wealth Continuity Dharma" and a contemporary representative of Newari-style thangkas from Nepal.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the combination of the "Five Directional Wealth Deities" (Yellow, White, Red, Green, Black) is far more than a simple "fortune-attracting symbol"; it is a "Wisdom & Blessing Provision System" centered on the "five directions and five elements."

As the central main deity, Yellow Jambhala is the collective manifestation of "merit in body, speech, mind, and good karma"; the other four deities correspond to the east, south, west, and north, symbolizing the balanced convergence of the five elemental energies (earth, wood, fire, metal, water). The core doctrine of this theme is "using wealth as a path to enlightenment": wealth is not an object of greed, but a "favorable condition" for practice—by worshiping the deities, believers obtain material provisions to focus on Dharma practice and perform generous almsgiving, ultimately achieving the perfection of "nurturing virtue with wealth, and accumulating wealth with virtue."

The composition of this thangka (main deity at the center, attendants surrounding it) is a visual expression of "five directional energies converging toward the center," which not only responds to believers’ wishes for worldly wealth but also implies the religious meaning of "perfection of five blessings."

Yellow Jambhala (Tibetan: "Zangla Serpo") is the core deity in Tibetan wealth deity beliefs. Its form strictly adheres to the protocols of the Iconographic Measurement Sutra, and every detail carries profound meaning:

The prototype of Yellow Jambhala traces back to Kubera, the wealth deity of ancient Indian Brahmanism. Later absorbed into Buddhism as an incarnation of Vaishravana (the Guardian King of the North), it gradually localized during the Yuan Dynasty (first appearing as a main deity in the murals of the Alxa Grottoes, symbolizing the protection of ethnic prosperity), and eventually became the "compassionate incarnation" of Ratnasambhava Buddha—Gautama Buddha once entrusted it to "protect the poor and suffering sentient beings," so it possesses both the deterrence of a Dharma protector and the compassion of a Bodhisattva.

-

Bright Yellow Body: Corresponding to the central "earth" element, it symbolizes a stable foundation of wealth like the earth;

-

Five-Buddha Crown: The five-leaf crown atop its head represents the wisdom blessings of the Five Dhyani Buddhas, implying the integration of wealth and wisdom;

-

Large Belly, Compact Body: This is not a "gluttonous appearance," but a symbol of compassion that embraces poor sentient beings, echoing the life wisdom that "a broad heart attracts good fortune";

-

Half-Lotus Posture: One leg is crossed, the other hangs naturally, with the right foot resting on a white conch—the conch symbolizes "retrieving treasures from the sea" in Buddhism, implying mastering the laws of wealth with wisdom;

-

Symbolism of Held Objects: The right hand holds a wish-fulfilling jewel (Cintāmaṇi, symbolizing fulfilling sentient beings’ reasonable wishes), while the left arm cradles a "treasure-vomiting rat (Nure)"—the rat holds jewels in its mouth, symbolizing "abundance through giving" rather than hoarding wealth.

The four wealth deities surrounding the main deity are subdivisions of Yellow Jambhala’s "collective energy," each with its own incarnation origin and exclusive merits:

Incarnated from Akshobhya Buddha (East), its emerald green body corresponds to the vital energy of the "wood" element. In the thangka, it holds a wish-fulfilling fruit—its core merit is "granting worldly wealth and increasing Dharma wealth": it not only secures material foundations but also enhances spiritual wisdom, making it especially suitable for those starting their careers, symbolizing "balance between material and spiritual wealth."

An incarnation of Amitabha Buddha (West) and a core wealth deity of the Sakya sect, its vermilion body corresponds to the dynamic energy of the "fire" element. Holding a wish-fulfilling jewel with a slightly wrathful expression, it governs "gathering social connections and attracting virtuous wealth": practice requires the initial intention of "benefiting others," otherwise it may breed afflictions, making it a blessing deity for businessmen or those needing to expand their networks.

Incarnated from the tear of Avalokiteshvara’s right eye, its milky white body corresponds to the pure energy of the "metal" element. In the thangka, it rides a flood dragon (symbolizing "overcoming poverty barriers") and holds a treasure scepter and treasure-vomiting rat. Its merit is "alleviating poverty and increasing good karma": it not only improves material poverty but also eliminates psychological barriers caused by poverty, making it a profound practice method for "believers starting from destitution."

An incarnation of Vajrasattva Akshobhya (East), its deep black body corresponds to the flowing energy of the "water" element, appearing in a wrathful form with one foot resting on a subdued creature. It is the "swiftest in bestowing wealth" among the five directional deities, governing "dispelling disasters, removing obstacles, and turning danger into safety"—but it has the highest practice threshold: it requires the premise of "non-greed and non-stinginess, otherwise one may be 反噬 by"ill-gotten wealth,"symbolizing that"wealth must be governed by good intentions."

This thangka is a classic representative of the Newari style from Nepal—Newari thangkas originated in the Kathmandu royal court, once exclusively for royal and noble worship, and are now treasured in museums worldwide. Their craftsmanship and style have distinct regional characteristics:

The pigments used in the thangka are sourced from natural minerals and earth materials in the Himalayas: yellow from orpiment, red from cinnabar, blue from Afghan lapis lazuli (classified into "first-grade lapis" and "second-grade lapis"), green from malachite, and white from ground deep-sea tridacna shells.

The preparation process is particularly elaborate: minerals must be ground to fine particles of 5-20μm, then mixed with cow glue aged for over 5 years at a 3:1 ratio—after the molecular chains of aged glue degrade, its viscosity decreases but ductility increases by 50%, preventing pigment embrittlement. These pigments have a lightfastness rating of ISO 7-8; after 300 years of simulated light exposure, they fade by only 2.3%, which is the core secret of thangkas remaining "as good as new for centuries."

This thangka follows 12 traditional Newari processes: using Nepalese linen as the base, repeatedly applying white mud paste and polishing to fill coarse fabric textures; sketching the underdrawing strictly according to the 37:25 golden ratio of the Iconographic Measurement Sutra; achieving color transitions with the "pinkie-controlled 晕染 radius" technique; outlining crowns and clothing patterns with 24K gold juice (15-20% concentration), with gold foil only 0.12μm thick, balancing grandeur and delicacy.

Compared to Tibetan local thangkas, its features are distinct:

-

Dense Composition: Details are refined to "jewel textures and treasure-vomiting rat fur," yet negative space from clouds and flowers creates a balance of density and sparsity;

-

Decorative Patternization: Clothing patterns and scrollwork are composed of curved lines, combining the dynamism of Indian art with the solemnity of Buddhist protocols;

-

Three-Dimensional Rendering: The "wheat-awn brush dotting" technique uses multiple layers of mineral pigments to give the deity’s body a three-dimensional texture.

The value of this thangka lies in the "unity of religious function and artistic value": from a religious perspective, it is a spiritual vessel for "using wealth as a path to enlightenment"; from an artistic perspective, it is a contemporary inheritance of Newari craftsmanship—nowadays, high-quality mineral pigment sources (such as lapis lazuli) are depleted, and only dozens of traditional Newari painters remain, so the collectible value of such hand-painted mineral pigment thangkas is rising year by year.

Notes for worship and maintenance: Avoid direct sunlight (though mineral pigments are lightfast, minimize UV damage); gently wipe dust with a clean soft cloth, do not use chemical cleaners; hang in a dry, ventilated area to avoid dampness and mold.

This Nepalese painted thangka is both a "mobile shrine," carrying the wealth wisdom of Tibetan Buddhism, and a "frozen color epic," recording Nepal’s millennial painting artistry.

#NepaleseYellowJambhalaThangka #FiveDirectionalWealthDeitiesThangkaAnalysis #NewariThangkaCraft #TibetanBuddhistWealthContinuityDharma #MineralPigmentThangkaCollection #HandPaintedThangkaArt #PaintedThangkaArt