The Mandala in Tibetan Buddhism: A Microcosmic Mirror of the Universe, a Sacred Temple for Spiritual Practice

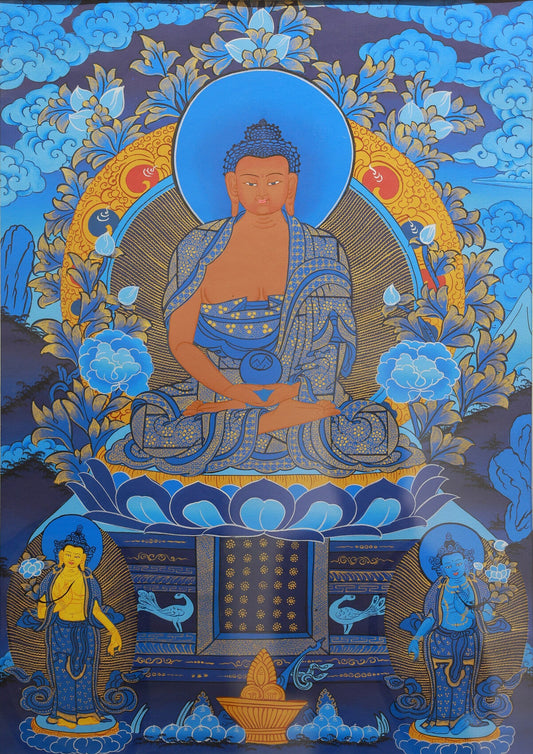

In the cultural genealogy of Tibetan Buddhism, the mandala is a symbol with both visual impact and spiritual depth. With intricate geometric patterns, rich colors and rigorous composition, it constructs a condensed cosmic landscape; it is both a sacred tool for monks' practice and a concrete expression of Tibetan Buddhism's cosmology and worldview. When one's gaze falls on that mandala Thangka with a bright yellow background and adorned with turquoise and sapphire patterns, the central lotus and Dharma image, the layered mandala barriers, and the surrounding auspicious decorations seem to instantly draw people into a spiritual dimension beyond the secular world. The mandala in Tibetan Buddhism has never been a mere work of art, but a "spiritual temple" leading to enlightenment.

I. The Origin of the Mandala: Evolution from Indian Tantric Buddhism to Tibet

The Sanskrit word for mandala is "Mandala", which literally means "circle" or "altar". It originally originated from the tantric practice tradition of ancient India. During the Vedic period in India, people held sacrificial rituals on circular altars, believing that the circle is the most authentic form of the universe, capable of communicating heaven and earth and connecting humans and gods. With the development of Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism combined the mandala with the belief in "Yidam" (Buddhist deity), defining the mandala as the "abode of the Yidam". Through visualizing the mandala, practitioners enter a state of unity with the Yidam.

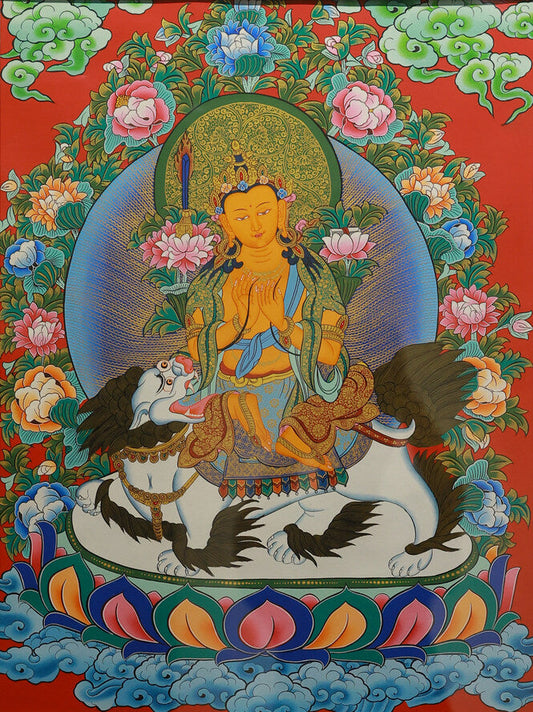

In the 7th century, Buddhism was introduced to Tibet, and mandala culture also took root there, deeply integrating with the local Bon culture of Tibet and the nature worship of the snow-capped region, forming a unique Tibetan mandala system. Major sects of Tibetan Buddhism, such as the Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, and Gelug, have different interpretations and applications of the mandala: the Nyingma School emphasizes the implication of "primordial purity" of the mandala, the Gelug School stresses the "precepts and order" of the mandala, and the Sakya School closely combines the mandala with the practice of the "Path and Fruit" method. From the simple altars in India to the elaborate sand mandalas, Thangka mandalas, and bronze mandalas in Tibet, the mandala is not only the evolution of religious symbols but also a vivid embodiment of the localization of Tibetan Buddhism.

The development of the mandala in Tibetan Buddhism is also reflected in its "materialization" and "systematization". Mandalas in Indian Tantric Buddhism were mostly abstract geometric symbols, while Tibetan monks integrated images of Yidams, Dharma protectors, and Bodhisattvas into the mandala, making it a "living universe". For example, the mandala in the accompanying image has a Dharma image symbolizing purity and enlightenment at its center, a surrounding lotus representing transcendence from samsara, and outer geometric barriers implying the order and perfection of the universe. Every detail bears the doctrines and philosophical thoughts of Tibetan Buddhism.

II. The Symbolism of the Mandala: A Microcosmic Mirror of the Universe, a Spiritual Practice Map for the Mind

In the cosmology of Tibetan Buddhism, the mandala is a "microcosmic epitome of the universe". With its core composition of circles and squares, it interprets Tibetan Buddhism's understanding of the world: the circle represents the infinity and perfection of the universe, while the square symbolizes the stability and order of the earth. The combination of the two is the cosmic pattern of "heaven is round and earth is square".

Structurally, a mandala is usually divided into four layers: the center, the inner circle, the middle circle, and the outer circle, each with its unique symbolic meaning:

- Central Area: The core of the mandala, representing the "Dharmakaya Buddha", the origin of the universe and the noumenon of enlightenment. Like the mandala in the accompanying image, the Dharma image and lotus seat at the center symbolize the purity and perfection of the "Adi Buddha" (Primordial Buddha), the ultimate state pursued by practitioners.

- Inner Circle: Mostly surrounded by lotus petals, representing the "Sambhogakaya Buddha", the manifestation of enlightenment, symbolizing the wisdom and blessings obtained by practitioners through meditation.

- Middle Circle: The "barrier" of the mandala, dominated by geometric patterns and images of Dharma protectors, representing the "Nirmanakaya Buddha". It implies the protection and salvation of all sentient beings by the Dharma, and also symbolizes the afflictions and obstacles that need to be overcome on the path of practice.

- Outer Circle: Mostly decorated with flame or auspicious cloud patterns, representing the "Vajra Realm", symbolizing the power and inviolability of the Dharma, and also implying transcending secular constraints and entering a pure state of practice.

Beyond its cosmological symbolism, the mandala is a "spiritual practice map for the mind". Tibetan Buddhism holds that the human mind is like the universe, full of afflictions and distracting thoughts, and the structure of the mandala corresponds to the levels of the human mind: the Dharmakaya Buddha at the center represents the primordial purity of the mind, while the outer barriers represent afflictions such as greed, anger, and delusion in the mind. By visualizing the mandala, practitioners gradually "purify" from the outer circle to the inner circle, and finally reach the enlightened state at the center—a process that is the path of practice of "looking inward and breaking attachments".

For Tibetan Buddhist monks, visualizing the mandala is not only a method of practice but also an "immersive spiritual experience". They will gaze at a mandala Thangka in a quiet Buddhist hall or sit in front of a sand mandala, integrating their consciousness into the structure of the mandala, as if standing at the center of the universe and merging with the Yidam and the Dharma. This visualization is both a cognition of cosmic laws and a reshaping of the self-mind.

III. The Production of the Mandala: Sacredness Carved with Ingenuity, Impermanence Written with Sand Grains

Mandalas in Tibetan Buddhism are mainly divided into sand mandalas, Thangka mandalas, bronze mandalas, painted mandalas and other types, among which sand mandalas and Thangka mandalas are the most representative and best reflect the artistic and spiritual core of Tibetan Buddhism.

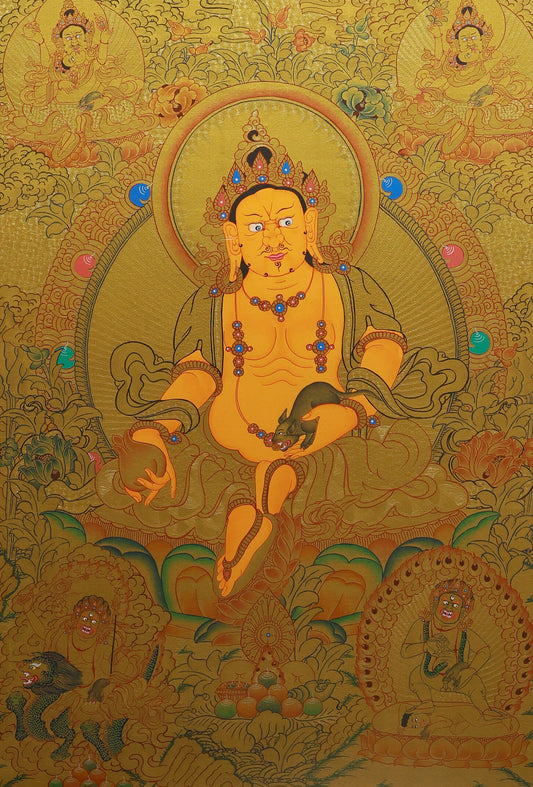

(1) Sand Mandala: Perfection in an Instant, Impermanence for Eternity

The sand mandala is the most ritualistic form of mandala in Tibetan Buddhism and the artistic creation that best embodies the doctrine of "impermanence". The materials for making a sand mandala are ground colored sand, mineral powder, and even gold powder. The colors are extracted from natural minerals: red from cinnabar, blue from lapis lazuli, green from malachite, and yellow from gold leaf. Each color symbolizes a different Buddhist implication: red represents compassion, blue represents wisdom, green represents vitality, and yellow represents perfection.

The process of making a sand mandala is a rigorous practice. It is usually completed by several skilled monks working together. Holding a special "sand tube" (called "chuba"), they let colored sand fall slowly from the tube through finger vibrations to outline the outline and patterns of the mandala. From the central Dharma image to the outer barriers, every stroke must be strictly in accordance with the inherited atlas without the slightest deviation. Making a sand mandala can take days or even months. Monks must keep their bodies and minds pure and undistracted, because they believe that the process of making a sand mandala is itself a practice.

What is most striking is the "destruction" ceremony of the sand mandala. After the mandala is completed and a blessing ceremony is held, the monks sweep away the colored sand with a broom, put the sand grains into a treasure bottle, and scatter them into rivers or mountains. This process interprets the core Buddhist doctrine of "anicca" (impermanence): all things in the world are formed by the combination of causes and conditions, and there is no eternal existence. Perfection is followed by dissipation, and true enlightenment is to see through this impermanence and let go of attachments.

(2) Thangka Mandala: Frozen Sacredness, Inherited Wisdom

Unlike the "instant perfection" of the sand mandala, the Thangka mandala is a "frozen mandala". With Thangka as its carrier, it permanently preserves the patterns and implications of the mandala, becoming an important ritual tool for worship and practice in Tibetan Buddhist temples and among believers.

The mandala in the accompanying image is a typical Thangka mandala work. With a bright yellow background, it symbolizes the light and perfection of the Dharma; the central Dharma image is surrounded by a lotus, representing purity and transcendence; the layered geometric barriers, mainly in turquoise and sapphire, outline the order of the universe; the outer golden decorations are like the Buddha's light, surrounding the entire mandala. Making such a mandala Thangka requires the painter to have profound religious literacy and painting skills: not only to accurately restore the mandala's atlas, but also to understand the symbolic meaning of each pattern, keep the body and mind pure during the painting process, and integrate the wisdom of the Dharma into the brush and ink.

The painting of mandala Thangkas follows strict "measurement scriptures". There are clear regulations on the proportion of the central Dharma image, the size of the barriers, and the details of the decorations. Painters must first learn the doctrines of Tibetan Buddhism and the measurement scriptures, and then undergo years of training before they can independently paint mandala Thangkas. A high-quality mandala Thangka is not only a work of art but also a carrier for the inheritance of Tibetan Buddhist wisdom. It bears the practice and insights of generations of monks and painters, becoming a bridge connecting the past and the present, the secular and the sacred.

IV. The Spiritual Practice Value of the Mandala: From Visualizing the Mandala to Contemplating the Inner Mind

In the practice system of Tibetan Buddhism, the core value of the mandala lies in "visualization practice". Whether it is a sand mandala or a Thangka mandala, it is a tool for practitioners to "look inward".

Tibetan Buddhism holds that practitioners can achieve three levels of improvement by visualizing the mandala:

The first level is "cognizing the universe". By visualizing the structure of the mandala, practitioners understand the order and laws of the universe, realize that all things in the world are formed by the combination of causes and conditions, and thus break the "attachment to self" and "attachment to Dharma".

The second level is "purifying the mind". Each layer of the mandala's barrier corresponds to the afflictions and attachments of the human mind. Practitioners visualize from the outer circle to the inner circle, just like gradually breaking the greed, anger, and delusion in the mind, allowing the mind to return to its primordial purity.

The third level is "unity with the Yidam". When practitioners visualize the Dharma image at the center of the mandala, they integrate their consciousness with the wisdom of the Yidam, achieving the practice goal of "attaining Buddhahood in this lifetime".

For contemporary people, the spiritual practice value of the mandala is not limited to the religious level, but can provide an enlightenment of "contemplating the inner mind" for the impetuous soul. In the fast-paced modern life, people are wrapped in desires and anxieties, just like being in the outer barrier of the mandala, bound by afflictions. The concepts of "looking inward" and "letting go of attachments" conveyed by the mandala remind us that true perfection is not in the pursuit of the outside world, but in the purity of the inner mind. We can learn from the wisdom of mandala visualization, set aside a quiet time for ourselves in the busy life, contemplate the distracting thoughts in the mind, break attachments, and find our own "spiritual mandala".

V. The Cultural Inheritance of the Mandala: A Sacred Symbol Sustained in Tradition and Modernity

Today, the mandala is not only a religious symbol of Tibetan Buddhism but also an important part of Tibetan culture. It has walked out of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and become a window for the world to understand Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan culture.

In Tibetan temples such as the Potala Palace, Jokhang Temple, and Tashilhunpo Monastery, mandala Thangkas and sand mandalas are still core religious ritual tools. Every year, ceremonies for making and praying for sand mandalas are held, inheriting the ancient practice traditions. At the same time, the artistic aesthetics of the mandala have been borrowed by modern art, and art museums and museums at home and abroad often hold mandala art exhibitions, allowing more people to feel the visual impact and spiritual connotation of the mandala.

In the digital age, the cultural inheritance of the mandala has ushered in new forms: innovative forms such as digital mandalas and 3D printed mandalas have emerged, allowing the mandala symbol to spread in a more modern way. However, no matter how the form changes, the "cosmology", "impermanence view" and "practice view" carried by the mandala have always been its core spiritual connotation.

The mandala in Tibetan Buddhism is a microcosmic mirror of the universe and a sacred temple for spiritual practice. It interprets the laws of the universe with intricate patterns, explains the doctrine of impermanence with the ritual of creation and destruction, and guides practitioners to look inward through visualization. For Tibetan Buddhist believers, the mandala is the path to enlightenment; for us, the mandala is a mirror that reflects the attachments in the mind and also guides us to find inner perfection. In this noisy era, the wisdom conveyed by the mandala, like the Buddha's light on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, is warm and firm, reminding us that true freedom comes from the purity and awakening of the inner mind.

#TibetanBuddhism #Mandala #TibetanCulture #BuddhistArt #SpiritualPractice #SandMandala #ThangkaMandala #TibetanBuddhistCulture #Cosmology #InnerMind

Tags:

Previous

Five-Wisdom Manjushri in Black-Gold Thangka: The Visual Code of Tibetan Buddhism’s Wisdom System

Next

Tibetan Buddhist Four-Armed Avalokiteshvara Gold Thangka: In-Depth Analysis of Compassion, Deity System, and Gold Thangka Craftsmanship