Padmasambhava: The "Second Buddha" of Tibetan Buddhism and the Founder of Himalayan Civilization

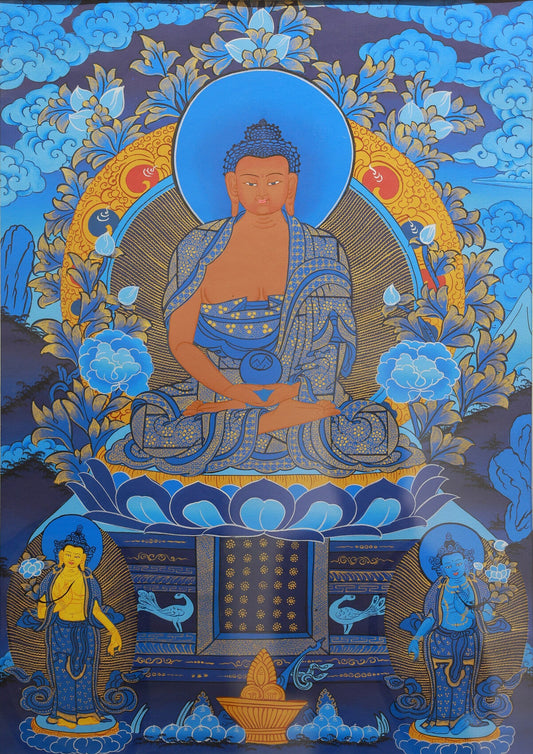

When a vivid Tibetan thangka unfolds, Padmasambhava—cloaked in saffron robes, holding a vajra and skull cup—sits half-lotus amidst a sea of lotuses. His dharma crown (adorned with sun and moon) symbolizes the union of wisdom and compassion; the trishula staff at his side embodies power to subdue demons; and the surrounding Buddhas and Bodhisattvas 印证 his identity as the "body of Amitabha, speech of Avalokiteshvara, mind of all Buddhas." In Tibetan Buddhism’s belief system, this saint, revered as Guru Rinpoche (Precious Teacher), has long transcended the role of "missionary" to become the spiritual totem of Himalayan civilization.

I. "Ocean-Born Vajra" from a Lotus: The Dual Dimensions of a Legendary Life

In Tibetan scriptures, Padmasambhava’s birth is a tantric parable: In the early 8th century, on the waters of Lake Dhanakosha in Oddiyana (modern Swat Valley, Pakistan), a blue lotus bloomed, and an 8-year-old child seated in its center emerged—an incarnation of the syllable Hrih from Amitabha’s heart, known as "Ocean-Born Vajra." This legend is rooted in reality: Oddiyana was one of India’s four great tantric sacred sites, and Padmasambhava’s royal background (adopted son of Oddiyana’s king) laid the foundation for his later dharma propagation.

Historically, Padmasambhava was a tantric master with both secular and spiritual authority: He ruled Oddiyana as a prince, but was exiled for "taming a demon minister’s son with illusionary methods." Later, he ordained under Shri Singha in Bengal, receiving the name Shakya Senge (Lion of the Shakyas). He traveled across India’s tantric sites, learned Dzogchen from Shri Singha, attained "lifetime nirvana" at Nalanda Monastery, and ultimately became "the greatest tantric master of Jambudvipa." This trajectory from royal power to spiritual authority foreshadows the "union of religion and politics" that would define Tibetan Buddhism.

II. Entering Tibet: The "Civilization Weaver" Reconciling Bon and Buddhism

In the mid-8th century, Tibetan Emperor Trisong Detsen faced a crisis: The Indian Buddhism he introduced clashed fiercely with Tibet’s indigenous Bon religion—Bon priests dismissed Buddhism as "foreign sorcery" after disasters like "flooded palaces" and "lightning-struck Red Hill." It was then that Shantarakshita recommended Padmasambhava: "This master can subdue Tibet’s evil spirits with fierce mantras, fulfilling the king’s wishes."

Padmasambhava’s journey to Tibet was a practice in cultural integration:

- Subjugation and Transformation: He converted Bon’s Twelve Danma Goddesses and Yarlha Shampo Mountain God into Buddhist protectors, preserving Tibet’s belief traditions while giving them new roles as "dharma guardians";

- Localization of Rituals: He adopted Bon practices like sang (incense offerings) and lucky flags, transforming them into Buddhist rituals;

- Doctrinal Adaptation: He merged Bon’s "three-world cosmology" with Buddhism’s "six realms of samsara," making abstract dharma teachings accessible to Tibetans.

This wisdom of "integrating Bon into Buddhism" not only resolved cultural conflicts but also rooted Buddhism in Tibet in a localized form—just as Bon ritual tools and Buddhist mudras coexist in Padmasambhava’s thangka, visualizing this fusion.

III. Samye Monastery: Tibetan Buddhism’s "First Temple" and Tantric Sanctuary

Trisong Detsen prepared Samye Monastery, Tibet’s first temple, as Padmasambhava’s "dharma propagation stage." This "Three-Style Temple" embodies Padmasambhava’s tantric philosophy:

- Mandala Structure: The central Utse Hall symbolizes Mount Meru, the four surrounding halls represent the four continents, and the circular outer wall is a "vajra ring," forming a tantric mandala;

- Multicultural Architecture: The ground floor is Tibetan-style, the middle Han-style, and the top Indian-style, reflecting the idea of "union of exoteric and esoteric, shared heritage of Han and India";

- The Origin of Terma: Padmasambhava buried the first batch of tantric scriptures in the monastery, initiating Tibetan Buddhism’s unique Terma tradition—these "time capsules" would be unearthed by tertöns (treasure revealers) when "conditions ripen," ensuring the purity of the dharma while leaving a spiritual legacy for future generations.

Though Samye Monastery is not directly depicted in the thangka, the wish-fulfilling tree in Padmasambhava’s skull cup symbolizes the temple’s role as a "wish-fulfiller"—after its completion, the first seven Tibetans ordained there as the "initial monks," marking the formal establishment of the Buddhist sangha in Tibet.

IV. Terma and Dzogchen: Padmasambhava’s Spiritual Legacy

Padmasambhava left far more than a monastery to Tibetan Buddhism. His Terma system is wisdom for the "Degenerate Age": hiding tantric scriptures in caves, lakes, or even practitioners’ consciousness to be unearthed by tertöns (often Padmasambhava’s incarnations). This transmission method avoids dharma distortion while keeping it "alive"—classics like The Life of Padmasambhava and The Tibetan Book of the Dead are mostly Terma works.

The Dzogchen teachings he propagated are the core of the Nyingma school: advocating "innate purity of mind, non-duality of clarity and emptiness," and enabling practitioners to achieve "enlightenment in this lifetime" through trekchö (cutting through delusion) and thögal (leaping beyond form). This "direct pointing to the mind" aligns with Padmasambhava’s thangka image—"vajra form in body, compassionate light in heart"—just as one of his eight manifestations, Wrathful Guru, subdues afflictions with a fierce appearance, embodying the tantric wisdom of "compassion expressed as wrath."

V. Padmasambhava in Thangka: A Dual Symbol of Faith and Art

Returning to the opening thangka, every detail of Padmasambhava’s iconography carries meaning:

- Dharma Crown: Adorned with sun and moon, representing the union of wisdom and skillful means;

- Vajra: Symbolizing power to shatter delusions;

- Skull Cup: Holding nectar and a longevity vase, meaning "attaining nirvana’s joy through the vessel of life and death";

- Trishula Staff: The three points correspond to "dharma body, sambhogakaya, nirmanakaya," representing the perfection of the three bodies.

These symbols construct a saintly image that is "both worldly and transcendental"—he is both a vajra warrior subduing demons and a compassionate guru guiding sentient beings. The thangka itself is a "visual practice" of Tibetan devotion to Padmasambhava: painting it is a tantric ritual, and enshrining it is a way to connect with his spirit.

Conclusion: Padmasambhava as the "Second Buddha"

In Tibetan Buddhism, Padmasambhava is called the "Second Buddha"—not as a replacement for Shakyamuni, but because he completed the Buddha’s unfinished work: spreading Buddhism to the Tibetan Plateau, making it the core of Himalayan civilization. From reconciling Bon and Buddhism to establishing the sangha, from initiating Terma to propagating Dzogchen, each step writes a model of "cultural dialogue."

Today, when Tibetans hold ceremonies on the 10th day of the 6th Tibetan month (Padmasambhava’s birthday), Padmasambhava in thangkas remains the center of faith—his image has long transcended history to become an "eternal presence" in Tibet’s spiritual world.

#Padmasambhava #TibetanBuddhism #SamyeMonastery #TermaTradition #DzogchenTeachings #BonBuddhistSyncretism #ThangkaArt #SecondBuddha #GuruRinpoche #HimalayanCivilization

Schlagwörter:

Vorherige

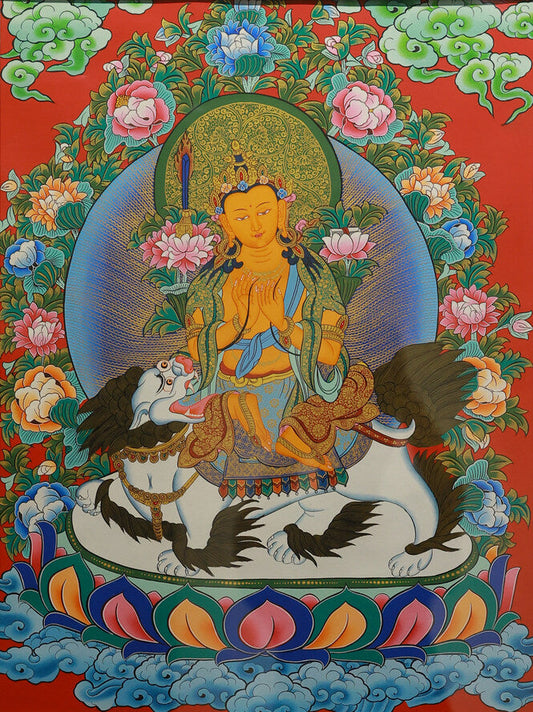

Amitabha Buddha in Tibetan Buddhism: Unlimited Light, Longevity, and Compassionate Guidance in Red Thangka Art

Nächste

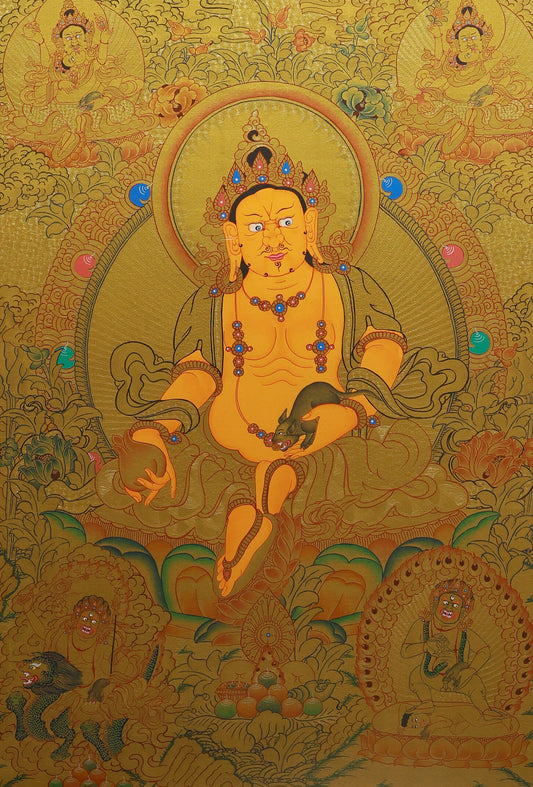

The Wisdom Deity in Black and Gold: Faith and Art of Manjushri in Tibetan Buddhism