The Dragon Mandala in Tibetan Buddhism: A Three-Dimensional Poem of Divine Oracle and Cosmos

When golden scales coil at the edge of a crimson mandala, the fangs do not snarl with malice—but instead breathe the dual divine oracle of "water and protection" in Tibetan Buddhism. This is the dragon mandala: an esoteric sacred object that forges dragon beliefs and mandala cosmology into a single compact form. In Tibetan monastery thangkas and spiritual practice ritual tools, the dragon mandala has never been mere ornamentation; it is the palace of water deities, a 结界 of dharma protectors, and a three-dimensional scripture through which practitioners visualize the transformation of "afflictions into wisdom."

I. The Visual Code of the Dragon Mandala: Folding the Cosmos from Golden Scales to Sanskrit

The composition of the dragon mandala before us is itself a precise arrangement of esoteric symbols:

The central "Om" syllable (ཨོཾ) is the primordial sound of the cosmos, enclosed in a vajra-patterned circle that echoes the esoteric core of "innate purity of mind." The red and black Sanskrit bands spreading outward form a textual matrix centered on the Dragon King Mantra—each character written in gold powder is a seal of the dragon dharma protectors’ vows. The outermost four golden-scaled wrathful dragons stand guard in the four directions: the blue pupils behind their fangs are the gaze of water deities, and their coiled bodies correspond to the Tibetan cosmic geography of "four rivers surrounding Mount Sumeru."

In Tibetan Buddhist art, the "dragon" is never a Chinese-style auspicious totem, but a dual figure of "water deity" and "dharma protector." The lines of the dragons’ manes and scales at the mandala’s edge follow strict rituals: golden scales symbolize "wealth and abundance" (dragons govern water sources and treasures), while fierce eyes represent "destroying obstacles" (the deterrent power of dharma protectors). The four-dragon layout directly aligns with esoteric texts recording the ritual of "four Dragon Kings guarding the mandala."

The profound meaning of this visual structure is annotated in the Vajraśekhara Sūtra, Chapter on Conditions: "A mandala takes the principal deity as its center, dharma protectors as its walls, and sentient beings’ minds as its foundation." Every curve and scale of the dragon mandala is a code that folds the "external cosmos" and "internal mind"—when a practitioner gazes at it, they see both the Dragon King’s palace and the transformation process in their own consciousness where "afflictions (the dragon’s ferocity) become wisdom (the dragon’s protection)."

II. The Cultural Roots of the Dragon Mandala: Symbiotic Beliefs of "Water and Dragons" in Tibet

Dragons in Tibetan Buddhism are never imported symbols; they are belief carriers deeply bound to the survival logic of the Tibetan plateau.

In Tibetan, vBrug (dragon) originally means "thunder," which is directly linked to Tibetans’ reverence for water: plateau precipitation and glacial meltwater determine pastures and harvests, and dragons are the masters of water. The Wish-Fulfilling Gem Tree Sutra describes the "Eight Great Dragon Kings" as natural deities who "govern rivers, lakes, and seas, and control rainfall and abundance." When Buddhism spread to Tibet, these indigenous water deities were not replaced but incorporated into the esoteric system as "dharma protectors"—the dragon mandala is the product of this "belief fusion": it is both a Buddhist mandala and a dragon temple.

This symbiosis is evident in Tibetan folk beliefs: farmers and herders offer dragon mandala thangkas during the rainy season to pray for the Dragon King to calm hailstorms; in monastery esoteric halls, dragon mandalas are often displayed alongside Dragon King Vases as core ritual tools for "calming disasters and increasing blessings." The Sanskrit texts on the mandala are mostly taken from the Dragon King Ritual Sutra, which records: "If this mantra is written in gold paste on the mandala, the Dragon King will be pleased and bestow 甘霖 (sweet rain) and treasures"—a textual reflection of this belief.

Notably, the "dragons" of the mandala are not a single group. In Tibetan esotericism, dragons are divided into three categories: "sky dragons" (dharma protectors), "sea dragons" (treasure guardians), and "earth dragons" (underground water stewards). The four dragons on the mandala correspond exactly to the "east, south, west, north" Dragon Kings: the eastern Anavatapta Dragon King governs "health," the southern Varuna Dragon King governs "wealth," the western Sagara Dragon King governs "wisdom," and the northern Manasvin Dragon King governs "peace"—each dragon on the mandala is a specific deity of well-being.

III. The Spiritual Practice Function of the Dragon Mandala: "Taming Afflictions" Through Visualization

For Tibetan Buddhist practitioners, the dragon mandala is never a "decorative object" but a "visualization tool" and "结界 (protective barrier) container."

In esoteric practice, "mandala visualization" is a core method: practitioners must construct a complete mandala structure in their minds, visualizing themselves as the principal deity and their surroundings as the mandala pure land. Dragon mandala visualization carries special "transformative" meaning—practitioners visualize "their own afflictions as fierce dragons," while the mandala’s scriptures and dragon forms are the process of "taming afflictions with mantra power and guarding the mind with dharma protectors."

Details of this visualization are specified in The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Esoteric Section): "When visualizing the dragon mandala, first visualize the central ‘Om’ syllable transforming into nectar, sprinkling over yourself to purify karmic obstacles; next, visualize the dragon scales transforming into vajra armor, protecting you from external demons; finally, visualize the dragon body transforming into a rainbow, merging into your mind to attain the Dragon King’s wisdom and power." This means every element of the dragon mandala is an anchor for the practitioner’s "mind transformation": golden scales are "firm bodhicitta," wrathful dragons are "vigor to destroy afflictions," and Sanskrit is "wisdom mantras."

Beyond individual practice, the dragon mandala is the core of collective rituals. In Tibet’s Dragon King Dharma Assemblies, monks place the dragon mandala at the center of the altar, offering butter sculptures and barley wine. When reciting the Dragon King Mantra, the dragon forms on the mandala are seen as symbols of the "Dragon King’s presence." After the assembly, if the mandala is sand-painted, monks pour the colored sand into rivers—this is both "dedication of merit to dragons and sentient beings" and a practice of "impermanence view": just as the dragon mandala dissipates, worldly blessings and afflictions are inherently illusory.

IV. The Modern Resonance of the Dragon Mandala: From Sacred Ritual Tool to Cultural Symbol

Today, the dragon mandala is no longer confined to monastery esoteric halls; it enters modern life as thangkas and decorative paintings, yet its "sacredness" remains intact—instead, it becomes a spiritual carrier connecting tradition and modernity.

In Tibetan homestays, hanging dragon mandala thangkas is seen as a way to "protect the home and attract blessings"; in urban zen spaces, simplified dragon mandala patterns are often used for decoration, their imagery of "flowing water" and "dragon protection" aligning with modern people’s dual desire for "stability and vitality." The art world interprets the dragon mandala as a "visualization of cosmology": its circular structure symbolizes "perfection," the dragon’s dynamism symbolizes "protection amid impermanence," and the static Sanskrit symbolizes "eternal wisdom"—this balance of "motion and stillness" is Tibetan Buddhism’s essential understanding of the world.

Yet we must remember: the core of the dragon mandala is always a "carrier of belief." When we admire its golden-scaled, crimson aesthetics, we should not forget the Tibetan herders’ reverence for water, practitioners’ contemplation of the mind, and the wisdom of "transforming natural deities into spiritual protectors"—a wisdom that may be the "balance" modern society needs most: like the dragon in the mandala, it must have the edge to destroy afflictions and the tenderness to guard life.

When golden scales fade into the crimson mandala, and Sanskrit mantras blur in the gaze, what we see is never just a work of art—but a three-dimensional poem woven by Tibetan Buddhism from "nature, belief, and mind." Every line of the dragon mandala is the plateau civilization’s answer to "how to coexist with heaven and earth in a harsh environment"—woven with reverence as the warp, wisdom as the weft, and protection as the knot, it finally forms a pure land landscape where "afflictions turn into sweet rain."

#TibetanBuddhism #DragonMandala #MandalaArt #EsotericBuddhism #TibetanBeliefs #BuddhistSymbols #SpiritualPracticeTools #DragonDharmaProtectors #ThangkaCulture #CosmicPhilosophy

Tags:

Previous

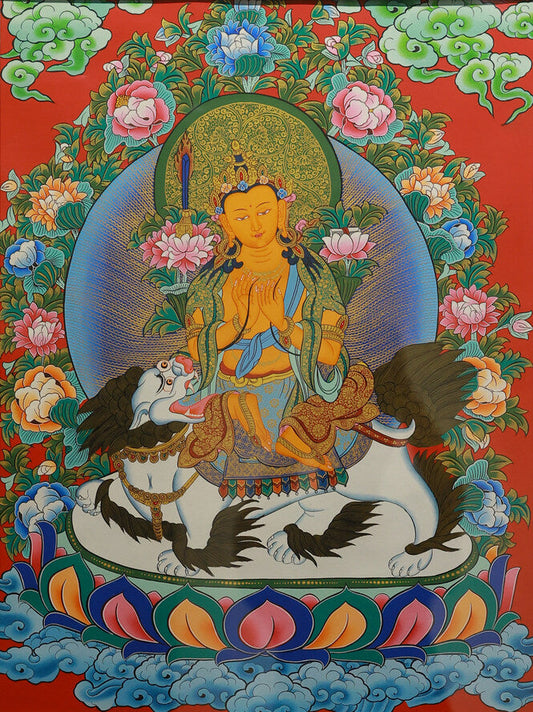

Cai Tang Vaishravana: The Guardian of Wealth in Tibetan Buddhism, The Golden Faith in Thangka Art

Next

The Green Tara in Silver Thangka: The Goddess of Compassion in Tibetan Buddhism, a Spiritual Guardian Across Millennia