A Prayer for Life Painted in Snowland Colors Decoding the Cultural Meaning of the White Tara Thangka

In the Tibetan Buddhist artistic tradition, a Thangka is never merely a painting.

It is a sacred image meant to be enshrined, contemplated, and revered—a visual medium through which prayers, compassion, and spiritual aspirations take form.

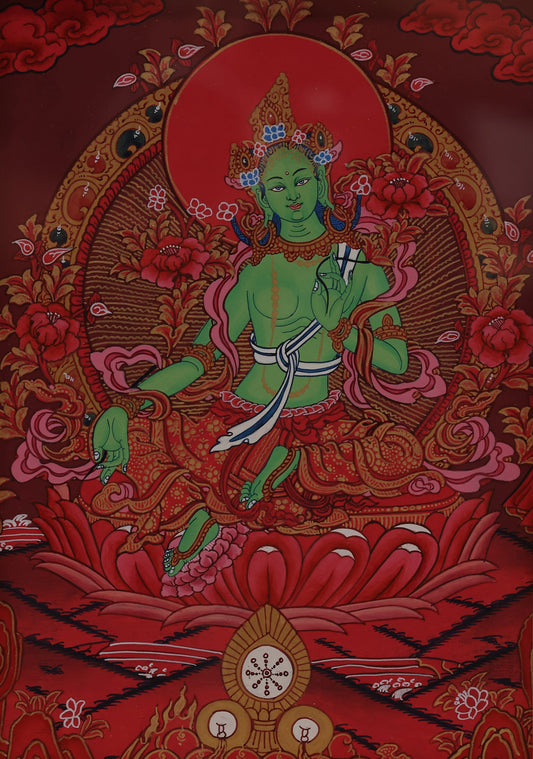

This hand-painted White Tara Thangka, centered on the Tibetan Buddhist ideals of longevity and compassion, stands as a classic example of traditional Tibetan color Thangka art. Its composition, iconography, and craftsmanship strictly follow ritual prescriptions while deeply reflecting the Tibetan cultural longing for life, well-being, and inner peace. It is often described as a “portable shrine” and a “mandala composed of color.”

I. The Core Theme: Compassionate Protection of the Three Deities of Longevity

The central theme of this Thangka is “the Blessings of White Tara and the Longevity Deities.” It belongs to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition of auspicious Thangkas, emphasizing the cultivation of both merit and wisdom.

In Tibetan culture, White Tara is regarded as an emanation of the tear shed from the left eye of Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig). She symbolizes boundless compassion, the liberation of suffering, and the bestowal of long life and health. Together with Amitayus (Buddha of Infinite Life) and Ushnishavijaya, she forms the revered “Three Deities of Longevity,” one of the most widely venerated blessing assemblies in Tibetan society.

The composition reflects the Tibetan Buddhist cosmological principle of “the central deity governing all directions.”

The main deity occupies the center of the image, while attendant deities are arranged around her—expressing both the hierarchical order of enlightened beings and the doctrinal belief that the main deity’s blessings extend throughout the six realms of existence.

Enshrining this Thangka is not merely a prayer for longevity, but a deeper spiritual aspiration:

the removal of obstacles, the cultivation of wisdom, and the attainment of inner stability. These aspirations resonate deeply with life on the Tibetan Plateau, where harsh natural conditions have long shaped a cultural emphasis on resilience, continuity, and spiritual refuge.

II. The Main Deity: Iconography and Symbolism of White Tara

At the center of the painting appears White Tara (Tibetan: Drolma Karpo), depicted in strict accordance with classical Buddhist iconometric scriptures. Every visual detail carries layered symbolic meaning.

1. Physical Form: The All-Seeing Compassion of the Seven Eyes

White Tara’s body is entirely white, symbolizing purity, clarity, and undefiled compassion.

Her most distinctive feature is her Seven Eyes—one on the forehead, two on the palms, and two on the soles of the feet—representing her all-encompassing awareness of the suffering of beings in all six realms.

This iconography is not meant to evoke mysticism, but rather to visually express unceasing awareness—compassion as the continuous act of seeing suffering without turning away.

2. Posture and Mudras: Compassion in Action

White Tara sits in full lotus posture upon a double lotus throne.

The lotus symbolizes purity arising unstained from worldly defilement, while the moon disc beneath her represents serenity, clarity, and mental calm.

Her right hand forms the Gesture of Supreme Giving, with the palm facing outward, signifying the fulfillment of the sincere wishes of sentient beings.

Her left hand forms the Gesture of the Three Jewels, holding a blue utpala flower whose stem rises toward her ear, symbolizing the nourishment of all beings through the Dharma.

3. Sacred Ornaments: Skillful Means of Compassion

Her jeweled crown, pearl garlands, and flowing celestial garments are not worldly decorations, but symbolic expressions of enlightened compassion manifesting through skillful means. In Tibetan Buddhism, compassion must appear in forms that beings can perceive and trust.

Thus, White Tara’s image is not only an artistic form but also a support for visualization practice. Through gazing upon her seven eyes, practitioners cultivate an inner experience of compassion extending throughout all realms, leading to mental ease and spiritual reassurance.

III. Attendant Deities: A Structured System of Spiritual Protection

The surrounding deities form a complete and coherent network of blessings, each occupying a specific ritual position.

Upper Deities: Source of Dharma and Longevity

At the top of the composition typically appear Shakyamuni Buddha, Amitayus, and Ushnishavijaya.

Shakyamuni Buddha represents the source of Buddhist teachings;

Amitayus embodies life extension and vitality;

Ushnishavijaya, holding a nectar vase, symbolizes purification and the removal of karmic obstacles.

Lower Attendants: Worldly Support and Protection

The lower section often features Yellow Jambhala or Green Jambhala, deities associated with material abundance and sustenance. Forms of Tara rescuing beings from specific dangers may also appear, reinforcing White Tara’s essential function as a liberator from suffering.

Side Attendants: The Union of Compassion and Wisdom

Flanking the central deity are commonly Four-Armed Avalokiteshvara and Manjushri, representing compassion and wisdom respectively. Together with White Tara, they complete the core Buddhist principle of the union of compassion and insight.

These figures are not arranged for aesthetic balance alone, but according to ritual logic:

the main deity provides fundamental blessings, while attendant deities address specific human concerns such as longevity, protection, and prosperity.

IV. Painting Craftsmanship: A Thousand-Year Covenant Between Nature and Devotion

The creation of this White Tara Thangka reflects a profound synthesis of traditional mineral-pigment techniques and religious discipline.

The canvas is made from hand-woven cotton cloth, repeatedly coated with animal glue and mineral gesso, then polished with stone. This method produces a resilient surface that resists aging and preserves the artwork for centuries. Scientific studies of Qing dynasty Thangkas preserved in the Palace Museum indicate that such canvases can remain stable for over 300 years.

All pigments are derived from natural sources:

white from highland clay,

red from cinnabar or coral powder,

blue and green from lapis lazuli and malachite refined through water-floating techniques.

Gold details are rendered using 24K gold powder, creating a luminous surface that shifts subtly with changing light—evoking the presence of sacred radiance.

During painting, extremely fine wolf-hair brushes are used to outline forms according to strict iconometric proportions. Colors are applied in multiple translucent layers using traditional shading methods, giving the image a gentle sense of depth and vitality.

Upon completion, a ritual “eye-opening” ceremony is performed, transforming the Thangka from an artwork into a fully consecrated sacred image suitable for veneration and meditation.

Conclusion: One Thangka, A Timeless Blessing for Life

A White Tara Thangka is far more than an object of visual beauty—it is a spiritual vessel.

It carries prayers for longevity, aspirations for compassion and wisdom, and a continuity of faith that transcends time.

Whether enshrined in a home altar, placed within a meditation space, or preserved as a cultural and artistic treasure, this Thangka quietly radiates protection and peace, transmitting the enduring light of compassion from the snowlands to the modern world.

#WhiteTara

#WhiteTaraThangka

#TibetanBuddhism

#TibetanThangka

#BuddhistArt#BodhisattvaThangka

#SacredArt

#BuddhistCulture

#HimalayanArt#Longevity

#Healing

#Compassion

#SpiritualProtection

#InnerPeace#MeditationArt

#SpiritualPractice

#BuddhistMeditation

#VisualizationPractice#HandPaintedThangka

#TraditionalThangka

#MineralPigments

#ReligiousArt