Vaishravana in Tibetan Buddhism: The Cultural Code of a Protector Deity Turned Wealth Guardian

wudimeng-Dec 30 2025-

0 comments

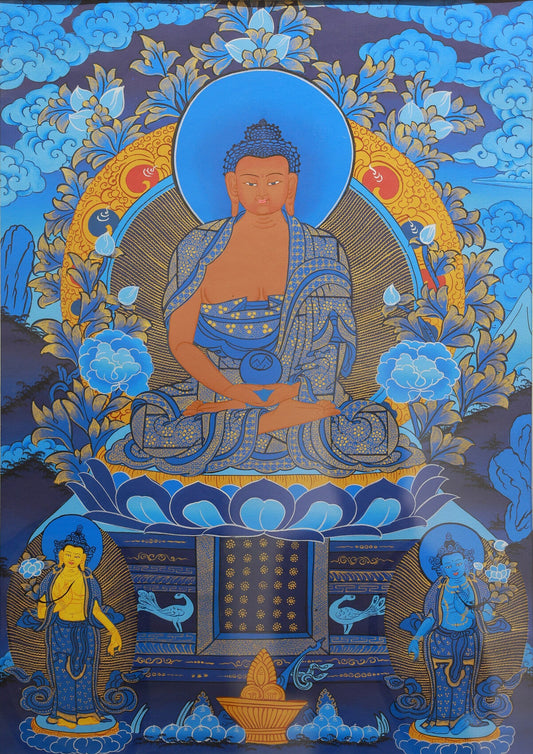

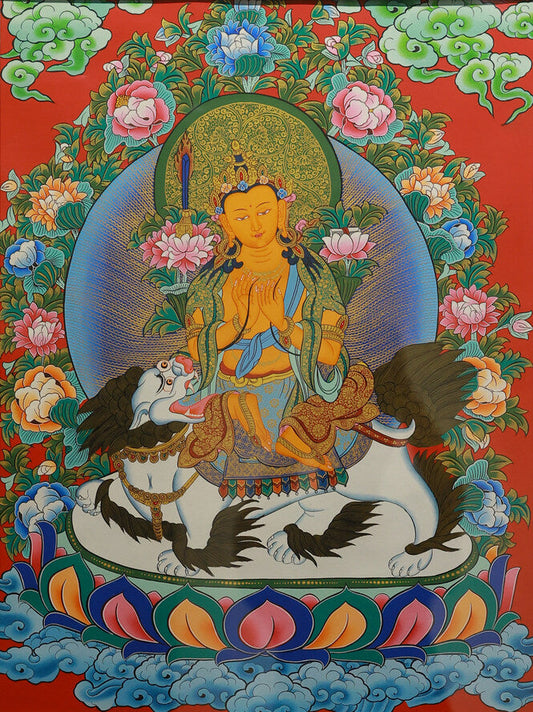

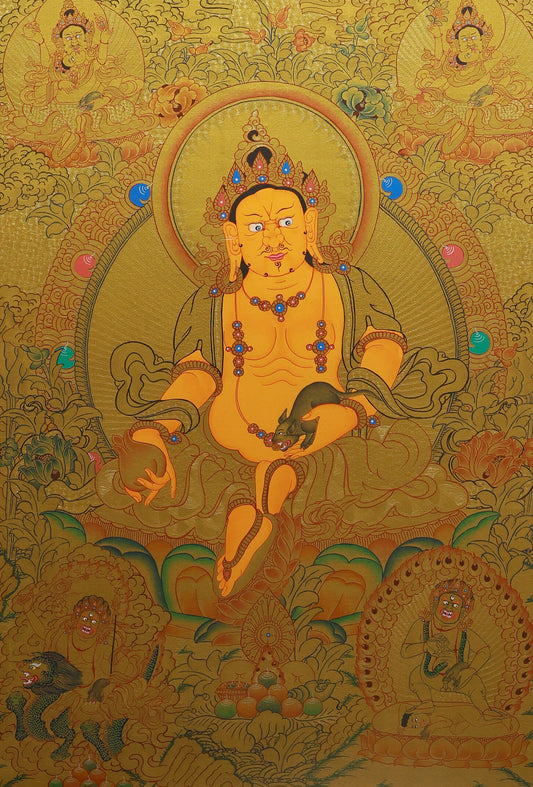

When you gaze at Vaishravana in a Tibetan Thangka—his golden figure mounted on a roaring white lion, right hand turning a victory banner, left hand holding a treasure-spitting mongoose that pours forth endless jewels, surrounded by treasure-bearing attendants and auspicious clouds—you are not just looking at a "wealth god." You are encountering a spiritual symbol that spans three dimensions in Tibetan Buddhism: protector, spiritual practice, and culture.

In the pantheon of Tibetan Buddhism, Vaishravana (Sanskrit: Vaishravana; Tibetan: Namthö Sé) is unique: he is both the "Northern Guardian King" who protects the northern continent of Jambudvipa (one of the Four Heavenly Kings), and a "wealth deity" who oversees the distribution of worldly riches, revered as one of Tibet’s most central wealth gods. This dual identity as "protector + wealth god" is the root of his enduring popularity.

Every detail in a Tibetan Thangka is a visual expression of doctrine. The Vaishravana in this Thangka contains a complete symbolic system:

-

Golden Form: In Tibetan tradition, yellow corresponds to the "earth element," symbolizing abundance and stability. It also aligns with his identity as an emanation of Ratnasambhava Buddha (the Buddha of "Perfect Blessings," who is depicted in yellow).

-

Right Hand: Victory Banner: Originally an ancient Indian military standard, the victory banner in Buddhism symbolizes "overcoming afflictions and obstacles." In Vaishravana’s hand, it extends to mean "endless flow of wealth"—turning the banner scatters worldly resources.

-

Left Hand: Treasure-spitting Mongoose: This white weasel (or rat) symbolizes "fulfilling desires," and its pouring jewels represent "giving wealth to sentient beings with a generous heart," rather than indulging greed. Notably, the treasure-spitting mongoose only appears in his "wealth deity" iconography; as a protector deity (the Four Heavenly King), Vaishravana does not hold this implement.

-

Mount: White Lion with Green Mane: The white lion symbolizes "subduing greed and obstacles," while the green mane corresponds to the "northern" direction. Its roaring posture reflects the protector deity’s authority, warning sentient beings not to lose their way amid wealth.

The attendants surrounding the main figure in the Thangka reveal Vaishravana’s "wealth management system":

-

Three Upper Figures: Typically a Buddha (like the Buddha in this image), a Bodhisattva (e.g., Vajrapani), and a guru—representing that "wealth originates from the protection of the Dharma."

-

Eight Horse-headed Wealth Gods: These eight subordinates oversee wealth from eight directions (e.g., the Yellow Wealth God of the East governs foundational resources; the Black Wealth God of the West transforms negative karma), each holding a treasure-spitting mongoose in their left hand, echoing the main deity’s role of "bestowing wealth."

-

Lower Auspicious Objects: The wish-fulfilling gem and Eight Auspicious Symbols symbolize "the union of material wealth and spiritual wisdom."

Vaishravana’s worship is not native to Tibet; it evolved through three layers of fusion: "Hinduism → Han Buddhism → Tibetan Buddhism."

His prototype is the Hindu wealth god Kubera, leader of the Yakshas, who governs northern wealth and resides in a gem-studded palace on the northern slope of Mount Meru. When Buddhism spread in India, he was adopted as a "protector deity" and renamed "Vaishravana" (meaning "well-heard," referring to his fame for blessings spreading far and wide).

During the Tang Dynasty, Vaishravana worship spread to China, where he was revered as a "war god"—legend has it he manifested to aid Tang troops during the An Lushan Rebellion. In Dunhuang murals, he is often depicted as a warrior holding a sword and pagoda, emphasizing "protecting the nation and Dharma" rather than bestowing wealth.

In the 11th century, Atisha brought Vaishravana practice to Tibet. Combined with Tibet’s need to "accumulate spiritual resources," his "wealth god" attributes were gradually emphasized:

- The Gelug school lists him as a "primary protector"; Tsongkhapa’s biography records that "Vaishravana bestowed treasures to help build Ganden Monastery."

- Among the people, he is linked to the "Five-colored Wealth Gods" (Yellow, White, Red, Black, Green) and regarded as the "leader of wealth gods"—the Five-colored Wealth Gods oversee specific wealth dimensions, while Vaishravana manages overall distribution.

Worshipping Vaishravana in Tibetan Buddhism is not about "seeking overnight riches" but following the core doctrine that "wealth is a resource for spiritual practice."

Scriptures clearly state two prerequisites for Vaishravana’s "bestowing wealth":

-

Pure Intention: Wealth must be sought to "support the Dharma and benefit sentient beings," not to satisfy personal desires.

-

Nurturing the Path with Wealth: Wealth should be used for offerings to the Three Jewels, alms to the poor, and building monasteries—not hoarded for pleasure. As Kagyu Jetsun Drolma said: "Blessings are not just money; if you have wealth but conflict in your family or afflictions in your mind, your blessings are still insufficient."

Tibetan Buddhism holds that poverty stems from "past karma of stinginess and non-generosity." Practicing Vaishravana’s method is essentially "clearing this karma and accumulating blessing resources":

- Basic rituals include reciting the mantra (Om Vaisravanaaya Svaha), water offerings, and lamp offerings.

- Advanced practice involves visualizing "oneself merging with Vaishravana, giving wealth to sentient beings with a generous heart" while repenting of stinginess.

Tibetan Buddhism strictly distinguishes between "seeking wealth" and "being greedy for wealth":

- It allows "seeking wealth to propagate the Dharma" (e.g., monks needing resources to build monasteries) but prohibits "seeking wealth for pleasure."

- Practicing with greed not only fails to receive blessings but also increases the affliction of "attachment to wealth." This is reflected in Vaishravana’s "mildly wrathful expression" in Thangkas—a warning that "wealth is a tool, not a goal."

Today, Vaishravana worship has transcended religion to become a fusion of Tibetan culture and commercial spirit:

Tibetan shops and families often display his Thangka or statue. Key worship points include:

- Facing north (aligning with his directional attribute).

- Offerings of clean water, Tibetan incense, and fruit (no meat or strong-smelling items).

- Wiping the statue and reciting the mantra on the 1st and 15th days of the lunar month, while practicing generosity (e.g., giving alms to beggars) to align with the "bestowing wealth" doctrine.

In Tibetan tourism and cultural and creative industries, Vaishravana often appears as a "symbol of good fortune": his elements can be seen in Thangka paintings, prayer wheel decorations, and jewelry designs. However, most creators note that "its core is ‘using wealth as a path’" to avoid being misinterpreted as a "symbol of 拜金 ism (worshipping money)."

When we appreciate Vaishravana in this Thangka, we should not see him as a "deity of desire satisfaction." Instead, he represents Tibetan Buddhism’s wisdom of balancing "worldly needs and ultimate liberation": wealth is a boat to cross the river of samsara, carrying sentient beings to accumulate resources and benefit others. Eventually, one must disembark to reach the middle path—"not attached to wealth, nor rejecting it."

This is perhaps why Vaishravana worship has endured for millennia: it responds to humanity’s simple longing for a good life, while using Buddhist wisdom to set boundaries, turning "seeking wealth" into part of "spiritual practice."

#TibetanBuddhism #Vaishravana #ThangkaArt #Kubera #TibetanWealthGod #WealthAsSpiritualPath #BuddhistProtectorDeity #TibetanSpirituality #ThangkaSymbols #BuddhistWealthPhilosophy